She changed Aviation history

Born: Hilda Beatrice Herbert. Also known as: Mrs Maurice Hewlett; Mrs Grace Bird

Sector: Aerospace and Defence

My knowledge of aviation history is exceedingly poor, so if you had asked me twelve months ago to name the first woman to qualify as a pilot in Britain, I would have said Amy Johnson. And I would have been wrong. Hilda Hewlett (1864-1943) got her wings in 1911, not five, not ten but eighteen years before Amy. And as well as training as a pilot, she opened a flying school and set up a plane manufacturing company that operated between 1912-1920. It was not what was expected in the Edwardian era from a 40-year old mother-of-two.

Born in Clapham on 17th February 1864, Hilda, known as Billy, had a strict upbringing. Her relationship with her father, a clergyman, was good but she did not get on well with her mother, Louisa. Before they married, her husband, Maurice, wrote to her: “I know that some people have the idea that the more miserable you make this life, the happier the next one will be, and I think your mother is one of these. It is a revival of the old system of hair shirts and peas in your shoes.” Billy was mainly home-schooled, then enrolled at the South Kensington Art School, but it was a three month-trip to Egypt when she was 19 that opened up the world to her: ‘I woke up from a narrow, conventional, stultifying childhood and first thought for myself’, she later wrote. On her return to London in 1883 she decided to train as a nurse and, in a show of independence, to do it in Berlin, where she spent a hard but happy year before being summoned home.

It was soon after this that she met Maurice Hewlett (1861-1923), trainee barrister and aspiring writer. They married on 3rd January 1888 in her father’s church, St Peter’s, in Vauxhall. They had a son, Francis, nicknamed Cecco, in January 1891 and a daughter, Barbara, known as Pia, in May 1895. For the first ten years of their marriage, Maurice held down his day job while writing in what spare time he could find. In 1898 came the breakthrough: the novel that he had been slaving over, ‘The Forest Lovers’, was published to huge acclaim, praised for its originality and its enthralling story-telling. He gave up his legal career to write full time and further successes quickly followed. ‘Mr Maurice Henry Hewlett stands out as one of the writers whose works will be known and appreciated a long way down the present century’, prophesied The Sketch incorrectly in January 1901.

Life became more interesting and glamorous. The couple started to attend weddings, gallery openings and theatre productions with the leading painters, actors and writers of the day, among them John Singer Sargent, Ellen Terry and Henry James. Billy went to dinner parties with Mark Twain and James McNeill Whistler. Sarah Bernhardt and Thomas Hardy came to tea. One particular friend was JM Barrie who named one of the pirates in ‘Peter Pan’ Cecco, after Francis Hewlett.

Thanks to Maurice’s writing they could move to a much larger house, 7 Northwick Terrace, near Lord’s Cricket Ground, which had a garage and an art studio for Billy. In 1899, she showed a metallic-effect screen in gesso on wood at an exhibition of decorative handicrafts staged by the Society of Women Artists and leatherwork at the Home Arts and Industries Exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall in 1900. When a dispute over the display of ‘The Light of the World’ drove William Holman Hunt to make another, much larger, version it was Billy, a friend and collaborator of his daughter, Gladys, who made the frame he had designed. Finally completed in 1904, the painting set off on a world-wide tour. It was purchased by Charles Booth who donated it to St Paul’s Cathedral in 1908.

However it was the garage that would prove more significant. The Hewletts became car owners and Billy threw herself into motoring, picking up speeding fines in May and June 1905. She loved the engineering challenges as much as the driving and was soon attracting attention.

The need for speed

In June 1906, Billy was a working passenger and mechanic for two trips with the pioneering motorcyclist Muriel Hind. The first was the annual London to Edinburgh trial, to be completed in less than 24 hours. Ten days later came a Reliability trial from Land’s End to John O’Groats, a six-day drive. Both were completed in a trip in a Singer tricar, which was a cross between a car and a motorcycle, looking something like this:

Sitting in the passenger seat at the front was a very exposed position…

A month later, Billy was in the driving seat for the Autocycle Club’s quarterly trial, a non-stop run of a 125 mile course around Uxbridge, where she made the second-fastest time on on leg up Dashwood Hill.

She carried on entering driving competitions but it was in 1909 that she discovered her true passion. In 1903, the Wright brothers had made their landmark flight at Kitty Hawk in North Carolina and while Billy was racing around the country, the aviation community was quickly growing. In July 1909, Louis Bleriot flew across the Channel. Harry Selfridge seized the opportunity to generate publicity for his new department store by displaying the plane. In August, 500,000 visitors attended an aviation festival in Rheims. The following month, Britain held its first aviation show in Blackpool. Billy attended and it ‘got hold of her’. She returned obsessed and announced to her husband that she wanted to learn to fly.

Enjoying this story? Subscribe to my newsletter or follow me on instagram to find out more about pioneering business women and their networks, as well as relevant exhibitions, talks, books and events.

Taking to the skies

At that point, there was nowhere in the UK offering flying lessons. Billy’s only option was to order her own plane from one of the construction firms in France and learn there. She raised the funds by selling some property and securing loans from family members and in January 1910 she headed to Mounmelon, where Farman was building its planes. There she joined Gustave Blondeau (1871-1965). They had been in Blackpool together, having probably met through the racing circuit and discovered they shared a passion for aviation. Whether there was also a passionate personal relationship is not clear but they decided to go into business together making planes. Maurice, concerned about the scandal and ridicule that might come with stories of his wife leaving her husband and two children to embrace this latest craze, insisted she train under a pseudonym, so she became Mrs Grace Bird.

Only one pupil could train per machine and Billy reluctantly agreed that Gustave went first as he was more likely to be able to start earning money in flying trails and competitions. There was not a warm welcome for women who wanted to fly and Billy was the only Englishwoman attempting to learn. She joined a bunch of daring adventurers who sat obsessively on the edge of the cold, muddy airfield, waiting for the flag to tell them that the wind conditions were in their favour. If conditions were unfavourable, she joined the men who packed into the grimy Aero Bar to learn aviation basics or dance off some pent-up energy.

Billy did not get into a plane, even as a passenger, until April 1910. She had to spend three long months building the plane she had paid for and watching others soar up into the clouds before she had her first glorious experience in the air. Storms and a crash destroyed Billy and Blondeau’s first two planes. In the summer of 1910 Billy and Blondeau returned to London, ‘with a white elephant and no elephant house, a pilot and no ground – and no money’.

They based themselves at Brooklands in Surrey and Billy joined the Royal Aero Club though quickly discovered that women were banned from all except one of the Club’s rooms.

The ‘Mrs Grace Bird’ identity was dropped when they set up the Hewlett and Blondeau Aviation School, which according to The Sketch in November 1910 was ‘flourishing’, with two pilots already qualified.

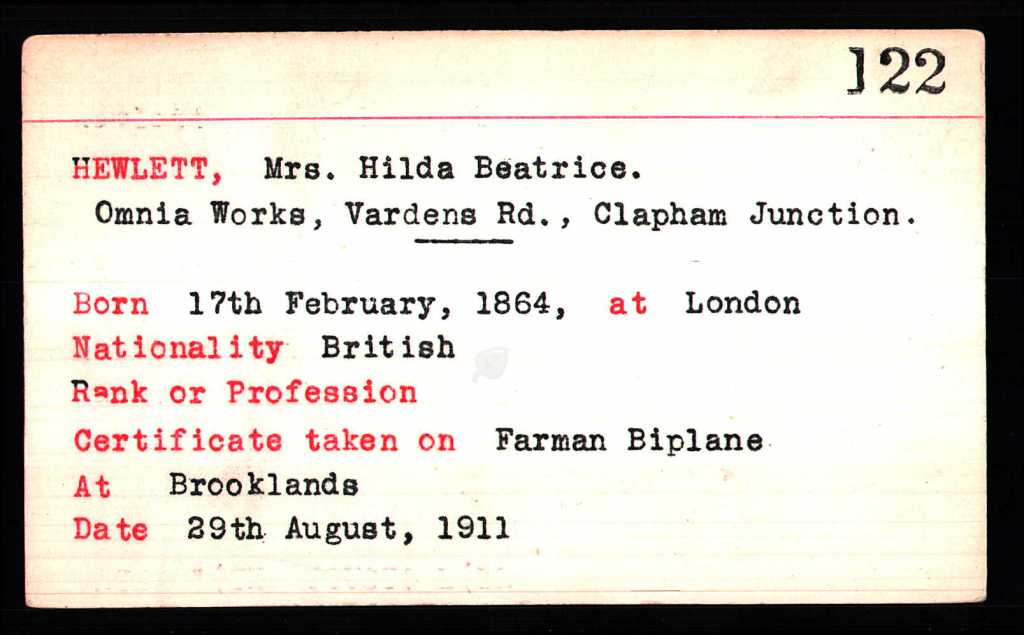

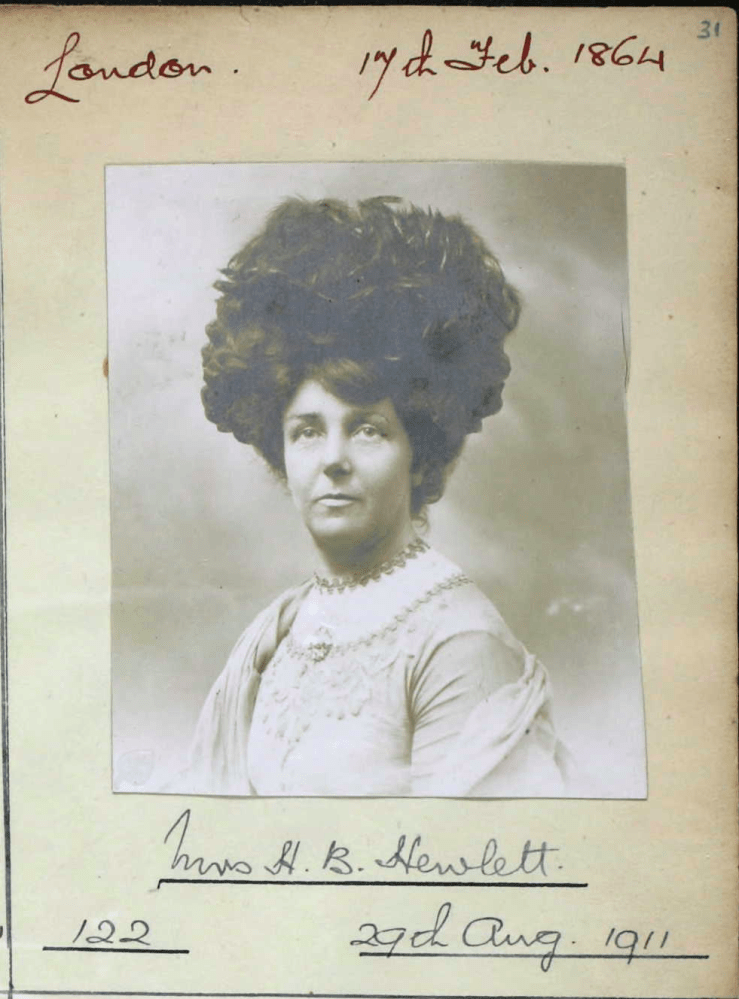

Billy and Gustave were living, or rather camping, in a cottage nearby, fitted out with the basics: camp beds, primus stoves, some pots and pans. Most waking hours were spent at the airfield. To supplement the income from the flying school, they built a small welding plant so they could offer repair services for planes and cars. In March 1911, they unveiled their second Farman plane. Billy was responsible for fitting all the canvas to the frame and it had a successful maiden flight, a new milestone for Brooklands. Meanwhile, Blondeau had been teaching Billy how to fly and in August 1911, she finally became the first woman to gain her pilot’s licence in Britain.

Billy’s children were swept along by her passion Her daughter, Pia, went up in the sky as a passenger and in November 1911, her son Cecco, now a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy, also qualified as a pilot. The story of a man being taught to fly by his mother caught the imagination, even if the truth was the majority of his instruction came from others. He became front-page news in the early days of the war after going missing during a raid on Cuxhhaven on Christmas Day, 1914 and was feared dead only to turn up six days later alive and well, having been rescued by a Dutch trawler. He was awarded the DSO.

The newspapers loved Billy. She is, said one, “a remarkably skilled and daring pilot.. She is an interesting personality, too, and her handsome sun-browned face framed in her aviator hood is very charming and full of character.” In July 1912, she gave an interview to the Pall Mall Gazette. She was asked if she was ever scared when she was up in the air. Her reply was clear:

“Aviators do not know what fear is. When you are up in the air, the exhilaration of flight and the necessity for careful control of your machine takes away all other feeling.”

Billy also shared the news that, with thirteen pupils now qualified, the flying school would be closing ‘as I wish to go in entirely for construction.’

The site she and Blondeau had found to build planes was an old skating rink on Vardans Road in Clapham, which they named the Omnia Works. The same paper went to see how she was getting on a year later. “Day after day from eight in the morning she is busy at her works” with orders from the War Office and the Admirality.

Their main models were Caudron biplanes and Hanriot two-seater monoplanes. “This practical woman aviator does all the canvas work, sewing, stretching, fitting, doping [waterproofing] and finally painting the colour which each inventor elects to sport so as to distinguish his planes from others.” They made the engine frames, not the engines or propellors, and built the designs of early manufacturers, like Farnham and Sopwith.

Billy was convinced that women could find profitable work in aviation manufacturing, viewing it as ‘delicate and exacting work for which they are quite fitted’ and thought they could also study the new science of aeronautics on equal terms with men. She had no truck with sexism and quit the Royal Aero Club after less than two years, saying “it has not been the slightest use to me.” The suffrage publications like Common Cause and Vote ran stories on her and one of the company’s planes was displayed at the Woman’s Kingdom exhibition, organised by the NUWSS in April 1914 but she was too busy to get involved in the movement and did not support the violent tactics of the suffragettes. When King George V opened the Aero exhibition in March 1914, she was aggrieved to be treated with suspicion by the police. Fearing she would launch some sort of attack, they tried to prevent her from reaching the company’s stand and when she forced her way through put two policemen on guard to keep her there until the King had left the building.

Business was going well. In April 1914, Hewlett and Blondeau became a registered limited company. Billy and Gustave held the majority of the shares but Maurice also invested. They started to look for much-needed new space and in May the Luton Reporter noted that ‘Messrs Hulett and Blondeau’ (sic) had bought land off Oak Road in Leagrave on which to build an aeroplane factory. The entire contents of Omnia Works was moved north. A new site was built, gas and water supplies secured and a telephone installed. And then, on 4th August, war was declared.

The war years

Production in Luton ramped up fast. The company quickly went from employing 25 staff to 300. This presented a whole new set of management challenges: expansion of the site; new working regulations imposed by the Ministry of Munitions; regular government inspections and as the war dragged on, shortages of both raw materials and skilled labour. Billy set up a training school to teach women the basics of aeroplane construction. It was such a success that it became an official centre under the auspices of the Ministry of Munitions, training women to work not only at Hewlett & Blondeau but at manufacturing plants around the country. It could take seventy students and the course lasted three months. A reporter for the Weekly Dispatch waxed lyrical:

‘There is something artistically pleasing in an aeroplane factory, with the soft continuous whir and whiz of the engines and the various mysterious parts of the monster bird. Hundreds of girls and women, in caps and overalls of blue, pink or heliotrope are busy. They are all deeply interested and concentrated on the work in hand… [performing] tasks which a few years ago aeroplane manufacturers would have declared they could never accomplish. There was, however, one manufacturer, Mrs Maurice Hewlett, who had vision of what was coming. She, as she started her own factory, prophesied that before long woman’s delicate touch and careful eye would be recognised as invaluable for certain parts of the work.’

Not everyone was so thrilled about this visible demonstration of female capability. In May 1917, the Amalgamated Society of Engineers supported a series of unofficial strikes to protest against the employment of unskilled workers, which caused a ten-day walk out of 73 staff at Hewlett & Blondeau. Within the factory, women who were learning new, and much-needed, skills like cable-splicing had their work returned to them by male supervisors as rejects. Billy told them to start inserting small pieces of red cotton so she could prove the rejected work had actually been made by other men. And then she fired the supervisors.

All change

The company kept operating after the war ended but demand for planes slumped and Billy and Gustave were unable to find another product to manufacture instead. They closed the factory in March 1920 and eventually sold the site to Electrolux in 1926. There is now a small street named Hewlett Road near Leagrave train station. Maurice died in 1923 and in 1927, Billy decided to emigrate to New Zealand. One of the last big events she attended before she left the country was the closing dinner for the Women’s Engineering Society annual conference, presided over by Laura Annie Willson, where the achievements of women on the road and in the sky were celebrated.

Both Pia and Cecco eventually joined Billy in New Zealand. She never lost her love of flying and became President of the Tauranga Aero Club. When she died in November 1943, some of the British papers marked the passing of the ‘First Woman Pilot’ but the stories were short or spent as much time talking about her son’s wartime exploits as her own.

Billy’s legacy

Hilda ‘Billy’ Hewlett was a true pioneer, an intrepid woman who refused to kow-tow to convention and deserves to be celebrated for her many and varied achievements. She is proof, if more is needed, that new technology is not just the province of the young and is an inspiration to anyone mid-way through their life who is considering a career pivot or striking out in an entirely new direction.

But her story could so easily have got lost. There are many reasons why women’s stories are given less space in the historical narrative. In Billy’s case, the main one was that she didn’t think what she was doing was particularly noteworthy. In March 1918 Lady Priscilla Norman CBE (1883-1964) visited the works of Hewlett & Blondeau in her capacity as Chair of the Women’s Work Sub-Committee, set up by the nascent Imperial War Museum to ensure the contribution of women to the war was properly documented. She and her team wanted to record the story and details of this unique enterprise but Billy would not play ball: “Many women have done more extraordinary things than taking a pilot’s certificate and running a firm. I have had so much help from others that I take no credit to myself.” The committee tried again: “I think perhaps… you do not realise that we are collecting for future generations more than for the present generation”, but Billy would not budge.

Fortunately, she did eventually write a memoir and it was this that made it possible for her grand-daughter-in-law, Gail Hewlett to write ‘Old Bird: The Irrepressible Mrs Hewlett’, the book that brought her back out of relative obscurity a decade ago. In 2015 Billy was celebrated with a plaque on Vardans Road, put up by the Battersea Society, in 2018 she was added to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, she features and her story is now regularly told at the Brooklands Museum as part of their schools education programme. She also appears on the City of Women London map, which re-imagines the London Underground map, replacing the names of stations with those of women and non-binary people who have shaped the city. A century after she turned down Lady Norman, Hilda ‘Billy’ Hewlett’s extraordinary doings have finally made it into the historical narrative.

Sources include:

The Queen 11/2/1899; The Era 15/4/1899; The Queen 2/6/1900; The Sketch 23/1/1901; The Daily News 9/3/1904; Morning Post 12/05/1905; The Sketch 23/11/1910; The Globe 9/10/1911; Bedfordshire Mercury 2/2/1912; The Tatler 3/7/1912; Pall Mall Gazette 6/7/1912; The Falkirk Herald 10/7/1912; Pall Mall Gazette 24/5/1913; The Luton Reporter 25/5/1914; Weekly Dispatch 25/3/1917; The Luton News & Bedfordshire Advertiser 20/9/1917; Stirling Observer 22/12/1917

‘The Letters of Maurice Hewlett’ ed. Laurence Binyon (1926); ‘Old Bird: The Irrepressible Mrs Hewlett’ by Gail Hewlett (2010);