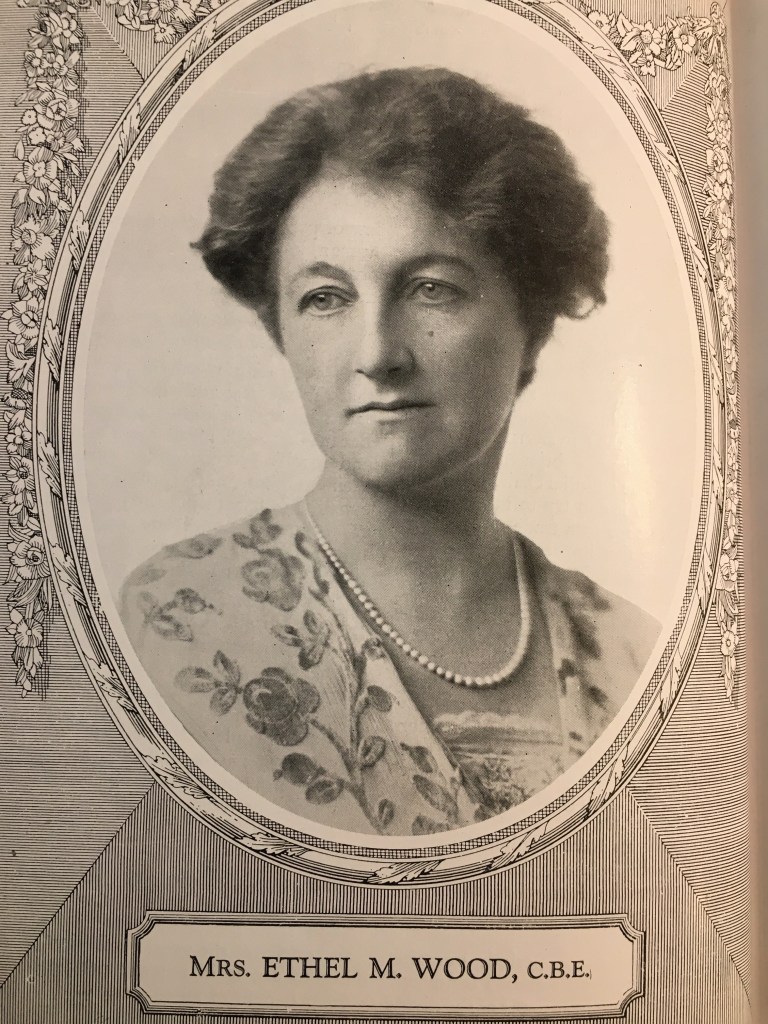

Born Ethel Mary Hogg; also known as Mrs H.F. Wood

Sector: Media (Advertising)

Every year King’s College London holds the Ethel M. Wood Memorial Lecture on Biblical Studies. As well as endowing the lecture in 1947, Ethel Wood gifted the university a priceless collection of over 400 bibles and books of biblical studies in 1950. Can this be the same Mrs E.M. Wood who was President of the Women’s Advertising Club of London in 1925? And the Mrs H.F. Wood who was awarded an OBE in the first Honours list in 1917 for her work on the London War Pensions Committee? As I have gradually found and put together all these seemingly unconnected pieces, a picture has slowly emerged of a woman with wide interests, boundless energy and a diverse network who was involved in such a wide range of organisations and projects over her long life that recognition for her achievements in any single one of them has eluded her.

Ethel was the fourth child of five born into an entrepreneurial family with deeply-held social values. Her father was Quintin Hogg (1845-1903), a tea merchant and founder of the Regent Street Polytechnic; her mother was Alice Graham (1846-1918), the eldest daughter of industrialist William Graham. He was a patron of Edward Burne-Jones and one of Ethel’s aunts, Frances, appears in ‘The Golden Stairs‘ while another, Agnes, married Gertrude Jekyll‘s brother, Herbert. Ethel’s eldest brother, Douglas Hogg, and nephew, Quintin Hogg, were both Lord Chancellors. Her cousin, Pamela Jekyll, married the politician Reginald McKenna, originator of the infamous Cat-and-Mouse Act. Her sister Elsie married into the Hoare banking family. There is no disputing that Ethel was well-connected.

Ethel’s parents were both educational philanthropists. In late 1885 the family moved to 5 Cavendish Square, acquired by her father as part of his purchase of the Polytechnic site at 309 Regent Street and in 1888 her mother founded the Young Women’s Christian Institute just around the corner. Family and polytechnic life were inextricably intertwined. Students trooped in and out of the house through the corridor that connected her father’s study to the Polytechnic gymnasium. Organisational milestones were the reason for family celebrations; family milestones, such as Quintin and Alice’s 25th wedding anniversary, were celebrated with students. Family homes in the countryside were used as a holiday destinations for students and later family holidays abroad were taken as part of students’ overseas trips.

However, despite education being the raison d’être of her parents’ lives, we know very little about Ethel’s schooling. She joined in social activities at the Young Women’s Christian Institute, competing in swimming competitions and offering fencing lessons, but was not a pupil there: the 1891 census suggests that she was taught by a governess. She does not seem to have gone to university and there are few details of what she was doing until her mid-20s but her father died suddenly when she was 25 and after some hesitation she agreed to write his biography, published in September 1904 to favourable reviews.

Love, marriage and war

In 1905 Ethel travelled to India, which is possibly where she met Herbert ‘Bertie’ Frederick Wood, a Captain in the 9th Lancers five years her junior. Bertie Wood was entrepreneurial and energetic, a crack polo player who became fascinated by flying and on 29th November 1910 became the 37th person in Britain to qualify as a pilot. He was later the founder and head of the Aviation section of Vickers Engineering. Their wedding on 14th February 1907 (the romantic date, in fact, a result of the wedding having to be abruptly postponed by five days due to Bertie’s father being ill) received plenty of coverage in the society pages.

It is possible that Ethel was a member of the one of the suffrage organisations before the war- she certainly had strong feminist views, spoke about SSFA, the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Family Association, at the International Women’s Franchise Club in 1915, was involved in a restaurant, Craig’s Court, in the 1920s that was a meeting point for suffrage organisations and spoke at a meeting of the Suffragette Fellowship in 1950 – but there is no definitive proof.

When war broke out Ethel took on a significant role at SSFA, now SSAFA, managing the SSFA office for the whole of London. At the start of the war, the organisation was responsible for distributing pensions but the Naval and Military War Pensions Act in 1915 changed all these arrangements and Ethel took on a significant role at the new London War Pensions Committee. She had only recently had a baby, Clemency Meara, born on 18th March 1915, and was now effectively the CEO of an organisation with around 700 men and women. The org managed all the work across London to take care of disabled men and motherless children, with general welfare responsibilities for the wives, widows and families of soldiers and sailors.

Ethel ‘worked at concert pitch all through the war’, ably supported by Major Robert Mitchell, who had been her father’s right-hand man at the Polytechnic. She later wrote his biography in 1934. Another important connection she made during this period was Francis Goodenough, a sales and marketing executive, who went on to work alongside Ethel on a number of other committees.

In August 1917 was among the first group of women to be given the new O.B.E. award along with Laura Annie Willson and Lena Ashwell. In June 1920, she received further recognition with a C.B.E. In 1919 it had emerged that her salary was £600 a year (c.£32,000 p.a. in 2022 terms), sparking some criticism but she was defended by the feminist press and the row was seen as exemplifying a broader issue about outdated attitudes to women’s pay, a theme to which Ethel herself would return many times over the coming decades.

Ethel’s work at the Pensions Committee finished in 1921. By now she was a single parent. Her husband survived the early fighting in France and then returned to London to focus on building Britain’s air force. He survived the war only to die of ‘flu and meningitis on 11th December 1918. Ethel was determined to keep working and had the means to move to 4 Park Village East, a spacious house just behind Regent’s Park which could accommodate a live-in governess and other household staff. She joined the team at the Daily Express organising the huge Woman’s Exhibition that opened at Earl’s Court in July 1922.

A new career in advertising

In October 1922 Ethel was appointed to the Board of Directors of Samson Clark & Co Ltd, a successful advertising agency founded in 1896 by Henry Samson Clark. He was a former member and long-time supporter of the Polytechnic as well as a family friend. Her new role attracted a lot of press attention. She shared her excitement a joining ‘a skilled profession..perhaps the most interesting of all’ with the Pall Mall Gazette and was intrigued by the number of questions she had had about women working in advertising.

‘It seems to me that most of the best achievements in the world are joint efforts, men and women both contributing something that helps. All “worthwhile” business has, must have, something of the creative in it, so why should we label this a “masculine” and that a “feminine” occupation?’

She was immediately very active in both the company and the wider sector. She was Vice President of the Regent Advertising Club, another Polytechnic-related initiative, and was one of the founder members of the Women’s Advertising Club of London (WACL) in September 1923.

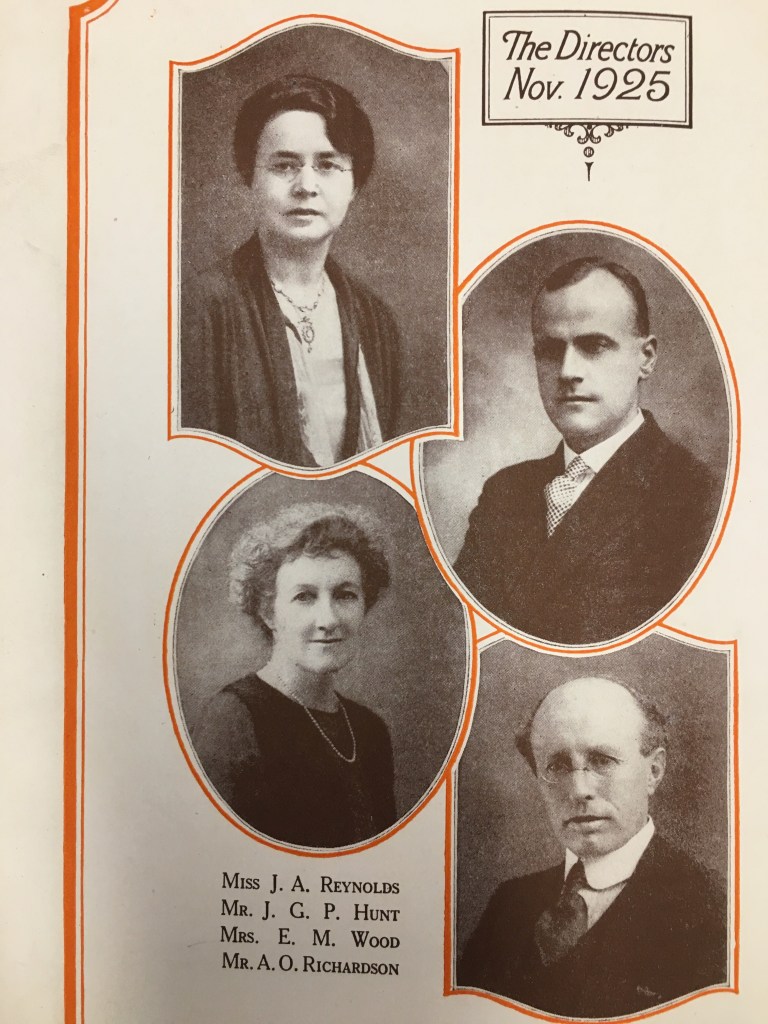

In February 1925, Samson Clark died suddenly while on holiday in Kenya. He left 30% of the business to long-time colleague, Jessie Reynolds, who had been a Director since 1912. Ethel was left 20%, putting the two women in control of what was by one of the largest advertising agents in the world. Later that year, Ethel became the third President of WACL. She was the only woman to speak at the first British Advertising Convention in Harrogate in 1925 and the only woman on the committee of the Advertising Association in 1926.

In 1926, Ethel edited the August edition of Advertising World. Working with Alice Head, the powerful editor of Good Housekeeping, she solicited contributions from Dorothy Cottington Taylor, head of the Good Housekeeping Institute, and one of their regular columnists, the barrister Helena Normanton. Her fellow WACL members Florence Sangster and Jean Lyon showed their support with their firms, W.S. Crawford and Punch, taking out full-page advertisements.

At a conference on New Careers for Women in 1928 Ethel spoke alongside Caroline Haslett and Gladys Burlton. While Caroline Haslett shared the story of a woman rejected from an engineering role because she was too attractive and would ‘upset’ the men, Ethel’s view was that in advertising ‘it doesn’t matter two hoots…whether an individual is a man or a woman so long as that person grows and can do the job.’

New thinking on business management

In the aftermath of the First World War, some companies wanted to discuss different approaches to management that were both more efficient and gave greater emphasis to workers’ welfare. In 1919, Seebohm Rowntree started a series of conferences were businesses could come together to share experience and in 1921 Charles Myers published ‘Mind and Work’ wand was appointed the first Director of the National Institute for Industrial Psychology. In 1927 the International Management Institute (IMI) was founded in Geneva as an independent offshoot of the International Labour Organization.

Ethel was clearly fascinated by these developments. In 1927 she became co-director of a data insight company that she set up with a former Liberal MP, Frank Gray and travelled out to Geneva to see what was going on for herself. During 1928 she started giving talks about the work they were doing and spoke at Rowntree’s 26th lecture conference, held at Balliol College in April of that year. She left her role at Samson Clark so she take on a voluntary role at the IMI and direct her energies towards this new passion: ensuring innovation in business and household management was not stifled by ‘the deadening hand of tradition’.

In 1929, she and Rowntree were two of ‘several prominent figures in British industry’ who represented Britain at an international conference on rationalisation of industry in Paris where the issues at hand were how to drive efficiencies in the iron, steel and coal industries. Ethel spent time in Birkenhead studying the working methods at Arthur Lee’s Tapestry Works as part of an investigation into their application of scientific methods in small factories. She was dismissive of describing employers’ responsibilities to their employees as ‘welfare work’: “[It] has a patronising sound, whereas care for the employee is simply good business for the employer.”

Ahead of the Fifth International Congress on Scientific Management in Amsterdam in 1932, she formed a heavyweight Committee for Domestic Science which included Dorothy Cottington Taylor, head of the Good Housekeeping Institute, Hélène Reynard, Warden of the King’s College of Household and Social Science and Caroline Haslett. Surveys were sent out to women across the country to find out more about their household spending patterns to develop model budgets and work was done to create ergonomic kitchens. She was also heavily involved in the Sixth Congress, held in London in 1935.

The Winter Distress League

As if Ethel did not have enough to do during the early 1920s, in parallel with her new role at Samson Clark in 1922 she also became Chair of the Finance and General Purposes Committee of the Winter Distress League. The brainchild of a Harrogate vicar, the charity was formed in the aftermath of the First World War to help the unemployed find work and to give children access to the countryside. The Executive Committee was chaired by George Lawson Johnston, son of the Bovril founder, and also involved were Robert Mitchell, Francis Goodenough and one of Ethel’s close friends, Clementine Waring, suggesting Ethel had a strong influence on its composition. She eventually ended up chairing it herself.

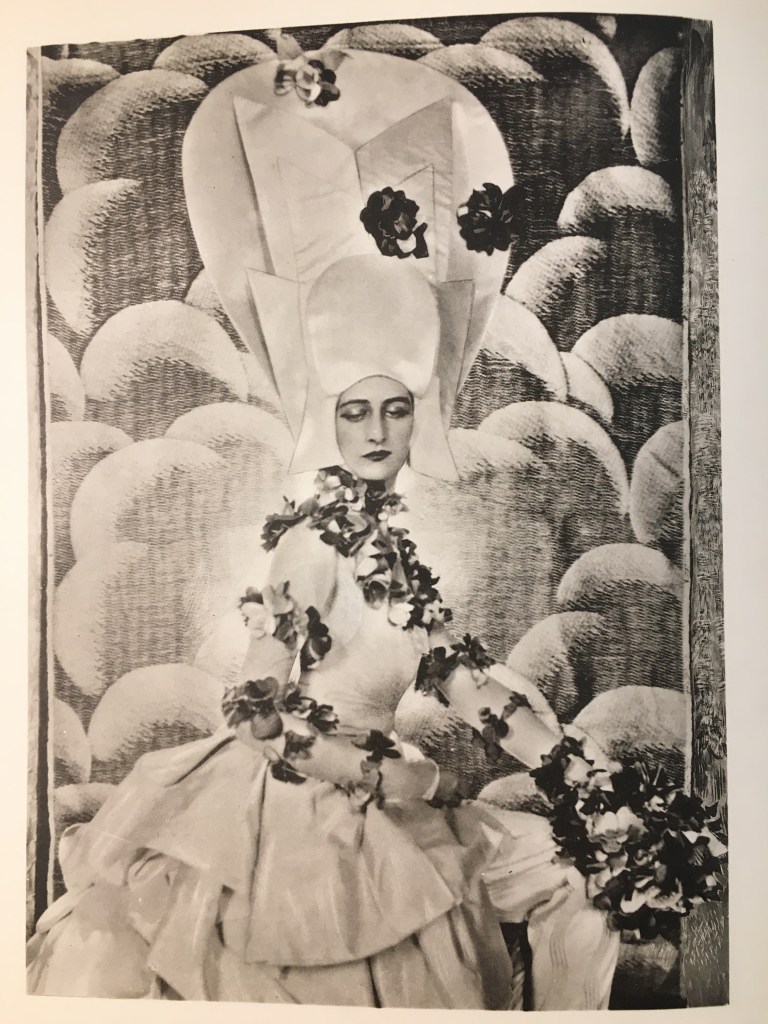

Ethel was actively involved in the fund-raising. She was on the committee that organised an annual summer fête at Devonshire House, along with one one of her sisters-in-law, and made BBC radio appeals on the charity’s behalf. In 1928, the League organised a ‘Dream of Fair Women’ pageant at Claridge’s Hotel for which a young Cecil Beaton designed a remarkable set of ‘Fashions of the Future’ including this Ascot dress for 2020. (Three years later the woman wearing it, Maxine Inigo-Freeman, left her husband for her flight instructor and became an aviation engineer).

A Norman Hartnell wedding dress that was also part of the pageant is now in the collection of the Museum of London.

With the founding of the Welfare State after the Second World War, the League reinvented itself as the Employment Fellowship and addressed the needs of those in retirement, continuing with its work until 2001.

Committee woman, policy pro

Speaking at the Annual Polytechnic Dinner in November 1951, Ethel remarked that one of the many oddities of British democracy was that members of governing bodies or Royal Commissions seemed to be selected for the interests they represented rather their expert knowledge, yet they still produced the results. By then she was in a very good position to make such an assessment.

Her first foray into the world of committees and commissions came in 1923, when she chaired the Domestic Service Committee set up by the Ministry of Labour to explore ‘the servant problem’, the shortage of domestic labour. In 1931 Clement Attlee, future Prime Minister but then Postmaster-General, was on a drive to increase the sales of telephones, then still the preserve of the affluent. He set up a small committee to advise on the publicity strategy. The members were a high-powered bunch: Margaret Havinden‘s boss, William Crawford; Stephen Tallents, who two years later would found the GPO film unit, a powerful force in British documentary film-making; Francis Goodenough; and obviously Ethel. In 1933 she was appointed to a re-constituted Food Council and in August the following year she agreed to sit on a committee advising the Milk Marketing Board on how best to spend its publicity budget.

Ethel worked with politicians across all political parties but later in her life, after the disastrous performance of the Liberal party in the 1945 General Election, she was chosen to be part of an ‘inquest’ into their defeat “though perhaps it would be more appropriate it they were to arraign themselves on a charge of attempted suicide”, commented one paper wryly.

Women of influence

Speaking late in November 1933 to a group of school pupils, she emphasised the importance of purposeful work and the perils of drifting: “None of us can think of a state of life in which there is nothing left to strive after.” One thing Ethel strived for throughout her life was equality of women’s rights and particularly of pay and over the course of her working life while her energy for this topic remained undimmed, speaking about it well into her 70s, she seems to have travelled the path from optimist to cynic.

A brilliant networker and a founder member of the Women’s Provisional Club (WPC), full of influential women, which held its first meeting Samson Clark’s offices in 1924. Lady Rhondda was appointed the first President and Ethel was Honorary Secretary, a post she held until 1962. She was also Secretary of the British Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs, working alongside Caroline Haslett.

In 1940 she became Honorary Secretary of the Committee on Woman Power. Chaired by Irene Ward, this pressure group brought together union representatives, business women and women from all the political parties to fight for women’s interests in the Second World War.

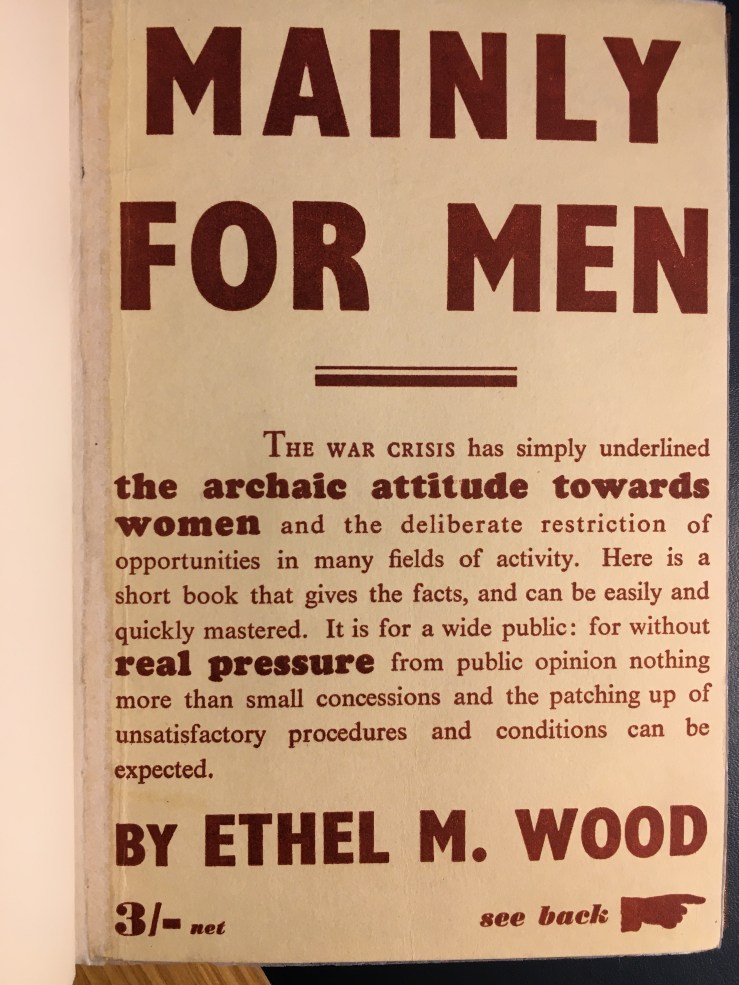

In 1943 Ethel wrote ‘Mainly for Men’ on behalf of the Committee.

Woman Power, in Ethel’s opinion, was the total contribution women could make in the world if only they were allowed to do so, equally with me. And based on what she had seen during the war, it was still a very big if. Committees were formed making decisions on issues that affected women without any input from women. Food, Health, Education and Labour were all key areas where women had almost no voice.

The book was aimed to mobilise public opinion: ‘It is a book for everyone to read who feels that women, equally with men, should take a share in shaping a new Britain after the war’, commented one (female) reviewer.

She followed this up in 1949, with ‘Pilgrimage of Perseverance’, a history of women’s journey to emancipation and was clearly disillusioned: concluding in her final chapter, ‘So What’, that ‘women as citizens find themselves in a man-fashioned and man-governed world’, where powerful institutions like the Civil Service, the Church, the Stock Exchange and banks were unrepentant die-hards and others withheld practical equality in more subtle ways.

The following year she joined with fellow militants in Kensington at meeting of the Suffragette Fellowship to discuss women’s progress over the last forty years. Helena Normanton was there, in fiery form, expressing her disappointment in women M.P.s and failing to address what she saw as one of the most critical issues, equal pay. She thought the answer was a women’s party. Ethel agreed with her that women had not done enough with their vote and urged them to “wake up and make use of that valuable tool.” She agreed “if women stood together over equal pay they would have it within a week,” she declared. It would be another 65 years before a version of their idea came to fruition with the formation of the Women’s Equality Party.

Back at the Poly

After the war Ethel reverted to her roots and returned to an institution where she had much more influence and nearly always received a warm welcome, the Polytechnic. In October 1945 she joined the Governing Body and became Honorary President of the Women’s Institute. She was also on the Committee for a major Fundraising appeal, attended Founder’ Day Teas, where she made speeches that ‘charmed and delighted everyone present’, a warm and friendly woman who spoke with fluency, wit and uninhibited candour. She wrote a history of the Polytechnic in 1965. In her final years she spent time with her many great-nieces and nephews, unconcerned by them racing around the corridors of her London club, celebrating their successes with them.

Ethel died of myocardial failure on her 93rd birthday, 29th June, in 1970. Her death certificate (incorrectly) recorded her year of birth as 1876 and her husband’s name as Bertram. In the introduction to her father’s biography, Ethel bemoaned the difficulty of conveying his personality when he had kept so little personal material – no journal, no diary, few private letters. History has largely repeated itself but the picture that emerges from reports of her work, her public speeches, published writing and family memories is of a resilient and generous woman with deeply-held values, forthright views and boundless energy. Ethel’s faith was clearly a mainstay and later in her life she became a Christian Scientist.

Sources include:

Archives: For the Polytechnic: University of Westminster Archives; Polytechnic Magazine;

For the Women’s Provisional Club: The Women’s Library Archives – London School of Economics; For Samson Clark and the Women’s Advertising Club of London – the History of Advertising Trust Archives

‘Mainly for Men’ by Ethel M. Wood (1943); ‘The Pilgrimage of Perseverance’ by Ethel M Wood (1949)

Gentlewoman 23/2/1907; Votes for Women 12/11/1915; The Vote 27/10/1922; Pall Mall Gazette 1/11/1922; 16/1/1923; The Tatler 4/7/1923; Aberdeen Press and Journal 28/2/1928; Hull Daily Mail 10/3/1928; Western Morning News 14/5/1928; Daily Telegraph 17/6/1929; Liverpool Echo 6/7/1929; Midland Daily Telegraph 26/6/1931; The Scotsman 13/1/1932; West Middlesex Gazette 11/11/1933; Aberdeen Press and Journal 9/12/1933; Northern Whig and Belfast Post 9/8/1934; North Wales Weekly News 25/11/1943; The Kensington News and West London Times 10/2/1950