Born: Fanny Rollo Wilkinson

Sector: Retail

In 2023, women garden designers outnumbered men at the Chelsea Flower Show for the first time in its 110-year history. Of the women who first made a career out of gardening, Gertrude Jekyll, who transformed domestic garden design, is well-known but Fanny Wilkinson, her contemporary, who was best known for her work transforming public spaces, is a less familiar name. This year’s Chelsea show included an installation celebrating women in horticulture. Fanny was not among them. However, she left her mark on parks and public gardens across London and trained a new generation of women horticulturists.

Fanny was born in Manchester in 1855. Her father, Dr Matthew Wilkinson, was a well-regarded doctor and wealthy, partly due to his own work but mainly as a result of inheritance. Her mother, his second wife, was American and Fanny was the oldest of the six children they had together. She grew up surrounded by open spaces. Her home in the Cholton-upon-Medlock area of Manchester would have had a spacious garden and she later moved to Middlethorpe Hall near York, with extensive grounds. It is not surprising that she developed an interesting in gardening but her decision to pursue it as a career was more unusual, even more so because there was no financial necessity for her to work. However her sister, Louisa, also wanted to pursue a career, as an artist and later as a bookbinder so they were clearly raised in an environment that encouraged independence.

In 1878, the passing of the Corporation of London (Open Spaces) Act meant that Corporation could acquire land within 25 miles of the City as open space for the recreation and enjoyment of the public. In 1881 this was extended to all other cities through the Metropolitan Open Spaces Act. That same year, Edward Milner founded the Crystal Palace School of Landscape Gardening and Practical Horticulture, which meant there was a route to learning other than through an apprenticeship, which would have been difficult for a woman to undertake. Landscape gardening was now a feasible career choice.

Fanny enrolled in an eighteen-month course in Crystal Palace in 1882. It meant moving to London and finding lodgings, an option open to Fanny due to her private income and made respectable by taking a companion, possibly Louisa. She lived in Bloomsbury, very near Agnes and Rhoda Garrett, and travelled to Sydenham each day by train. She wrote to her mother in December 1882 that the evenings were spent quietly, writing, reading and sewing, with occasional visits.

She was the only woman on the course and there are no other references to women studying here, all indications of Fanny’s determination and resilience. She studied park and garden design, both public and private, and also residential layout design. The same letter explains:

“I am at present engaged upon a manufacturing of lakes. Mr Milner considers they are the best practice for what I require. Are there any bridges required about the estate? I feel capable of designing a wooden one.’

Starting out

By the time she completed her course at the end of 1883 Fanny was perfectly positioned to work with the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association (MPGA), which by then had been up running for a couple of years. She remained in Bloomsbury and was enjoying London living, writing to her mother before Christmas in 1883 that and Louisa were both busy with work and had hosted a successful dinner:

“We had sardines & brown bread & butter; chicken & pork, potatoes, cauliflower au gratin, celery & beetroot salad, your two moulds as sweets. Cheese, figs & coffee. No beer or wine such was the repast.”

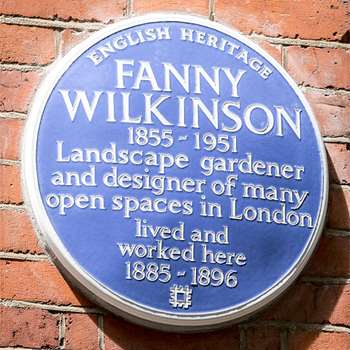

On 5th February 1884, the MPGA elected Fanny as a member and honorary landscape gardener. In 1885, she moved to 15 Bloomsbury Street (now 239/241 Shaftesbury Avenue) and used the sitting room as her office. Some of her early projects were within walking distance of her flat: Red Lion Square Gardens in Holborn, Paddington Street burial ground in Marylebone, St Bartholomew the Great in Smithfield, St Martin’s in the Fields on Trafalgar Square. Dressed in a skirt slightly shortened to avoid it dragging through the earth, she would measure the space and create the plans that would transform disused burial grounds and wasteland into squares and parks with trees, paths and flower beds. Some of her landscape plans were later exhibited in the ‘Women’s Art and Industry’ section of the Glasgow Exhibition in 1888 and the 1893 Chicago Exhibition.

She then submitted a quote for the job, which included her fee. Fanny was a vocal advocate of equal pay and was not prepared to accept any financial penalty for being a woman. Once given agreement to proceed, Fanny would oversee a team to do the work, normally a team of men. She preferred to put her own team together, comprised of men she knew would accept taking instruction from a woman but this was not always possible. Working outside gave her a tan that would have marked her out from her peers who spent most of their time inside and were protected by a parasol when outside.

Some of these early commissions were significant in scale. A major commission from the MGPA in 1888 was to transform 15 acres of land into a pleasure garden for residents in the East End, with a budget of £100,000 (c. £10m today). Schemes on this scale could see Fanny overseeing more than 200 workers.

By 1888 Fanny already had developed sufficient standing to be able to take trainees, who paid £100 a year for a two year apprenticeship. They included: Emmeline Sieveking, who laid out Octavia Hill‘s Red Cross Garden in Southwark (and also later married Fanny’s brother brother, Matthew); Madeline Agar, who became Principal of Swanley Horticultural College in 1922; and Lorrie Dunington, who set up her own landscape design business and lectured on the topic to the all-male classes at the Architectural Association. In 1911 she emigrated with her husband, another landscape architect, to Toronto where they set up a business together and undertook a range of local projects.

Building her portfolio

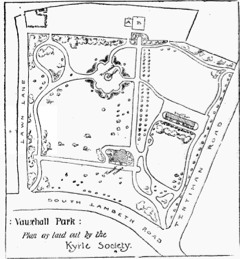

Although it was the MGPA that was the real driver of change in London’s urban landscape and Fanny’s major source of work – it estimated that she did around 75 projects for them – she also worked for another, smaller, group that had been equally active in campaigning for London’s green spaces, the Kyrle Society. Her most high-profile project for them was the development of Vauxhall Park, which began in around 1887. Henry and Millicent Fawcett had been living in a rented house, 51 The Lawns, since 1875, one of a houses with large gardens, Fanny knew the Fawcetts well. Back in December 1882, when Henry had been ill, she had written to her mother about his progress and the Royal concern shown in his health.

“The hamper from Sandringham contained 10 pheasants, 6 partridges, a wild hare and 2 duck. Is it not a truly royal present? The Prince of Wales sends very nice letters and telegrams. The Queen’s messages are all sent through her secretary. Her Majesty’s also come very expensive as they have to put so many words in, in answering. 1/6 and 1/9 a message.”

Henry had survived that scare but died two years later in 1884. Now the whole row of houses had been bought by a housing developer and the eight acres of green space looked destined to be lost. Supported by the Kyrle Society, Millicent Fawcett led a campaign to retain it as a green space for London. Sufficient funds were raised to purchase the site and Fanny was tasked with creating the design for this new park.

Her design catered to the needs of young and old with a playground and a sheltered seating area and is still an important community park today.

On Monday 7th July 1890, Vauxhall Park was formally opened by the Prince and Princess of Wales. Octavia Hill, Emma Cons and Millicent Fawcett were all present along with Millicent and Henry’s daughter, Philippa. (She had just become the first woman to achieve the top score in the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos exam but despite her score being 13% higher than the next nearest student, she was denied the honorary title of Senior Wrangler.) The Prince complimented Fanny on her work. By now her tanned skin would have marked her out from here peers who spent their days sheltering inside or protected by a parasol when outside.

Women’s organisations were another important source of work. She did projects for the Women’s University Settlement, Blackfriars, the Women’s School of Medicine the New Hospital for Women and the Girls Public Day School Trust. She also took on private commissions though no records exist to say how many of these projects she did, where they might have been or on what sort of scale. It is likely, though, that in these situations she would have been directing men who usually took instruction from a (male) head gardener and could well have been less than enthusiastic about taking direction from a woman. Still she seemed to manage these situations.

In 1896 she moved to 6 Gower Street, next door but one to Agnes Garrett. 1898: disused burial ground behind Robert Browning Hall, York Street in Walworth. 1899: Paragon Gardens New Kent Road plus Portland Place nearby; Albion Square public gardens in Dalston – hundredth project – Fanny – over 75.

Women’s Agricultural and Horticultural International Union – 1899

Later described as ‘a useful society with a long name’, the Women’s Agricultural and Horticultural International Union was formed in 1899. The initiative sprang from discussions held during the presentation of agricultural papers at the International Women’s Congress held in London that year. The inaugural committee was huge, with 27 members, mainly from the UK with the international element provided by three American women and one each from Belgium and Denmark. The goals of the organisation were to build community, share information, advise on training and secure better pay but this was not just about giving women a support network.

Women who were part of this group had real concerns about food security, in particular the level of reliance the UK had on imports of butter, cheese, eggs and poultry. One of the committee members, Ethel Tweedie, had written at length about this in 1895. She could perhaps have chosen a more compelling title than ‘Danish versus English Butter Making’, but the argument she laid out over 78 pages could not have been clearer: Britain needed to take heed at what other countries were doing and address its own agricultural policies and practices to avoid an over-reliance on food shipped in from other countries. There she had argued that mobilising women to re-claim an agricultural domain that traditionally had been theirs – overseeing the management of the farm dairy – could make a huge difference. More than a century ago, fat was already a feminist issue. The organisation’s first annual meeting was held at studio of painter and feminist Louise Jopling, another Congress attendee, and it affiliated to the National Union of Women Workers. Later reorganised into the Women’s Farm and Garden Union it still exists as the Working for Gardeners Association.

The move to the Garden of England

In 1901 Fanny visited the US with Theodora Powell to study US colleges and practices but further involvement was curtailed by her appointment as Principal of Swanley Horticultural College in Kent. Swanley first opened its doors to women in 1891, a move driven by Emma Cons. Fanny had been involved right from the start, sitting on the inaugural committee of the Ladies Branch in 1891 and acting as a judge in annual competitions. Newspapers were gently mocking about the prospects for women as market gardeners, nursery gardeners and retail gardeners. ‘Women are generally expert in making “beds” and ought to be quite at home in the nursery’. But by 1896, more women were applying than men and a number of high profile women had become involved in its governance. In 1902 the decision was made to become a women-only college, a remarkable shift in the space of ten years and Fanny was asked to take over as Principal and she re-located to Kent.

The re-organisation meant changes to the accommodation with a new bedroom layout in the main building and the closure of two of the smaller boarding houses that had been used by women. A new study space was created and the dining room was re-decorated. The permanent dairy instructor was appointed and plans made to expand the dairy operations and enlarge the herd. The curriculum was expanded to incorporate . but the biggest change was the decision to set up a Colonial branch with a version of the course that looked at horticultural in different climates.

She represented the College at conferences that explored the opportunities to grow the horticultural sector through education and training opportunities as well those addressing women’s access to work. By now Swanley was taking in between 30 and 45 pupils a year so had around 70 students at any one time. The fees already limited access to the wealthier but finding the money to cover both capital and running costs with no endowment was an ongoing challenge and fund-raising was another important part of her job.

In 1905, The Gentlewoman added Fanny to its ‘Roll of Honour for Women’, an ongoing project to ‘tell something of the strenuous lives of those who work to further objects of usefulness to the State or individual’. That year another ex-Swanley student, Madeline Agar took over from Fanny as landscape gardener to the MPGA. Now Fanny had to keep her green fingers happy by growing fruit and vegetables that she exhibited in shows.

When the First World War broke the warnings that had been given about food security proved only too real. By 1918, butter and cheese were rationed. Fanny retired from Swanley in 1916, giving her more time to focus on another area of war-time shortage: medicines. A reliance on imports from Central Europe – Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Balkans – had left dispensers struggling to get the drugs they needed to treat wounded soldiers and paying dearly for the supplies they could find. Fanny’s view was that women could fill the gap by turning over space in their gardens and allotments to cultivate monkshood and purple foxglove, fennel and valerian. She set up a Women’s Herb-Growing Association, a body of ‘practical women horticulturists’, affiliated to the Women’s Farm and Garden Union.

When Swanley ran into difficulties in the post-war years, Fanny agreed to return for a year in 1921 to help stabilise it. In 1922 she was replaced by Dr Kate Barrett, a former student and botanist, who stayed in post until 1944. After her second retirement, she still remained actively involved in horticulture and found a new interest, breeding goats. She died on 22nd January 1951, aged 95. In 2022, she was honoured with a blue plaque at 239-241 Shaftesbury Avenue.

The archives of the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association are held by London Metropolitan Archives. For more on Fanny Wilkinson’s projects for the MPGA, see ‘Enterprising Women: The Garretts and their Circle by Elizabeth Crawford (2002)

Other sources:

Borthwick Archives, University of York

St James Gazette 2/1/1888; Pall Mall Gazette 28/2/1890; South London Press 5/7/1890; The Queen 12/7/1890; Northern Whig 14/10/1890; Manchester Times 21/11/1890; London Evening Standard 20/5/1891; Dundee Evening Telegraph 29/6/1891; Bognor Regis Observer 9/11/1892; The Queen 27/1/1894; Evening Mail 18/6/1894; Westminster Gazette 14/7/1898; Middlesex Country Times 8/7/1899; Morning Post 13/7/1899; The Queen 17/3/1900; 18/4/1903; Bexley Heath and Bexley Observer 1/5/1903; The Gentlewoman 11/3/1905; Myra’s Journal of Dress and Fashion 1/5/1910; Kent & Sussex Courier 3/11/1916

‘The rise, decline and fall of landscape architecture education in the United Kingdom: A historical outline’ by Robert Holden; ‘A Triumph of Brains over Brute: Women and Science at the Horticultural College, Swanley, 1890-1910’ by Donald L Opitz (2013) Isis. 30-62.