Also known as M.V. Wheelhouse

Sector: Retail

One of the highlights of the British Empire Exhibition, which opened in April 1924, was a huge dolls’ house made for Queen Mary. Now displayed in Windsor Castle, it was designed by Edwin Lutyens and is still the largest dolls’ house in the world. It took three years to complete and over 1,500 artists, craftspeople, writers and decorators contributed to its construction, including Gertrude Jekyll, A.A.Milne and Gustav Holst. Rolls-Royce and Daimler provided custom-built cars, Cartier made a clock and the senior partner of Berry Brothers chose the wine.

During the seven months that it was on display at Wembley, it was seen by over 1.5 million people and any who looked closely at the day nursery would have seen a merry-go-round by the reputed company Pomona Toys.

(c) Royal Collections Trust RCIN 230272

Established in 1915, Pomona Toys was a joint venture between Mary Vermuyden Wheelhouse and Louise Jacobs (1880-1946). Though both were originally from the north of England, Mary born in Leeds, Louise in Hull, it most likely that they met through their suffrage activities in London.

Mary came from an artistic family: although her father earned his living as a surgeon, he had been an early pioneer of photography. One of her two older sisters was a well-regarded violinist. Mary was a Christmas baby, born on 12th December 1867 and baptised on Christmas Day. She loved drawing and painting and in 1895, when she was 28, she became a pupil at the Scarborough School of Art. Then she moved to Paris to spend three years studying at the Académie Delécluse. While she was there, her work was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London. The Académie was well-known as a supportive environment for women and it was here that the Women’s International Art Club (WIAC) was formed in 1898 and had its inaugural exhibition in London’s Grafton Galleries in 1900. Mary was a member, one of many women’s networks and organisations in which she was an active participant.

By 1901, she was living and working at the Pomona Studios on the New King’s Road, near Eel Brook Common. The building still stands, the name visible over the imposing entrance but where now there are high-end flats, a century ago there were three artists’ studios. She shared the building with a landscape painter, William Dickson, and an artistic couple, Charles Praetorius and his wife, who worked under her maiden name, Minnie Cormack.

Her main source of income during this period came from her work as an illustrator. She had a breakthrough when ‘The Adventures of Merrywink’, published in 1906, written by Christina Whyte and illustrated by Mary was named the best new story for girls. As well as the £100 prize, it brought a steady flow of commissions. She illustrated work by Charlotte Bronte, George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell and Louisa May Alcott, among others, and was particularly proud of her work on the Queen’s Treasures Series published by George Bell & Sons.

By then Mary had become one of the founders of the Artists’ Suffrage League, set up by Mary Lowndes in January 1907. A fifteen-minute walk separated the two women’s studios. Mary Lowndes was a talented stained glass maker. In 1906, together with her business partner, Alfred Drury, she built the Glass House on Lettice Road, a purpose-made working space for independent stained glass artists. (It only closed in 1993).

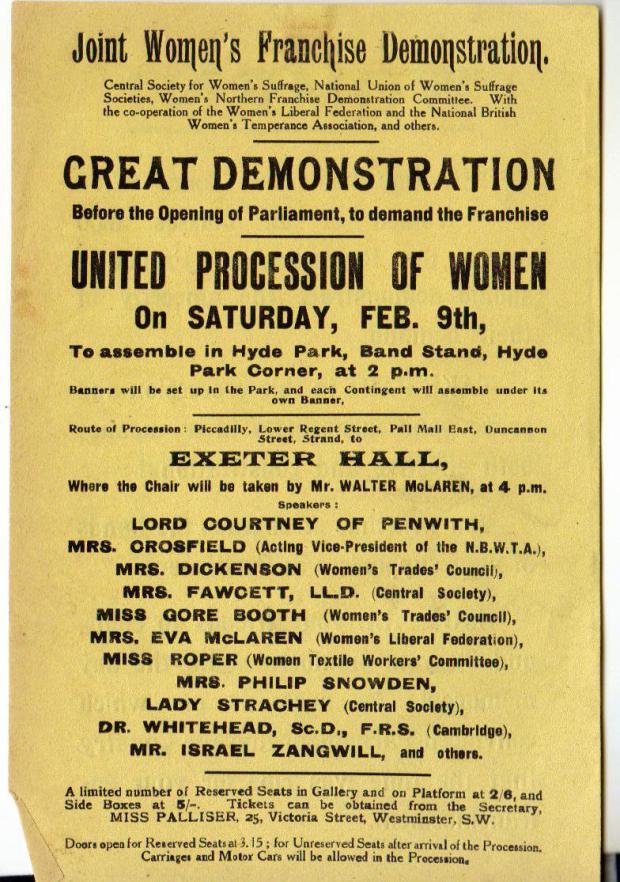

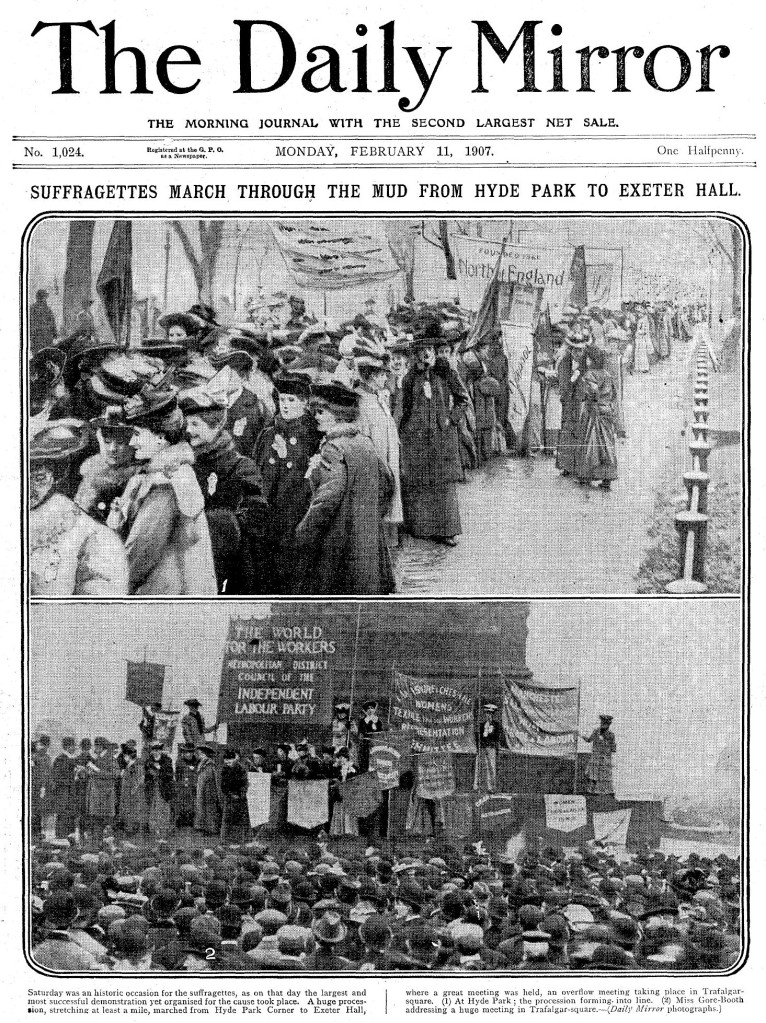

The reason for artists to come together was to make banners and signs for a landmark demonstration organised by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Later known as the Mud March, the huge procession through London from Hyde Park to Trafalgar Square on 9th February 1907 marked the start of a series of grand pro-suffrage processions that made headlines for the next seven years.

Mary’s first business partner was Louise Jacobs (1880-1946). They had a lot in common: like Mary, Louise was also from the north of England, born in Hull. She studied at the local School of Art and then at the =Royal College of Art in London. She also earned her living as an illustrator and painter, while spending spare time working as part of the Suffrage Atelier alongside Louise Jopling. She was responsible for an image that was so iconic it was quickly re-purposed by Harold Bird for the Women’s Anti-Suffrage League.

Postcard published by the Suffrage Atelier

The launch of Pomona Toys

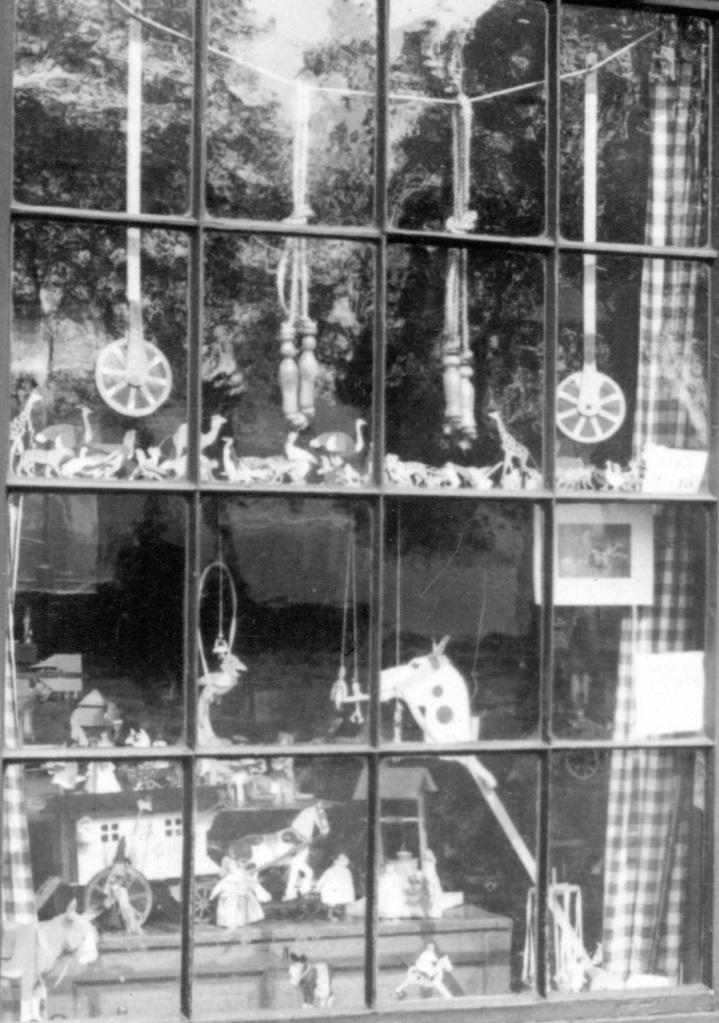

How Mary and Louise decided to join forces and enter the toy-making business is not entirely clear. Perhaps the outbreak of war and the consequent halt of pro-suffrage activities suddenly left them with time to devote to new ventures. They opened a store at 64 Cheyne Walk in 1915 and their toys received a rave write-up in the run up to their first trading Christmas. There was glowing praise for a dolls’ theatre, a flower shop with real sand and a plentiful supply of potted plants and a Covent Garden market cart laden with ‘supremely realistic’ vegetables.

‘In a corner of Chelsea..there is a door that opens into fairyland’. wrote The Bystander a year later, in its 1916 Christmas Shopping guide. ‘Children have been the first to discover it and a row of small faces glued to the window-panes is as stationary as the toys inside.’ Soft toys in the shape of elephants and seals for babies; a wooden Noah’s Ark waiting for wooden penguins and spotted flying fish; ‘manly toys of masculine youth’ – presumably cars and soldiers. There was something for everyone at ‘extremely reasonable’ prices. Their skill at putting a novel twist on an old classic won them plenty of fans. A Jack-in-the-Box sprung open to reveal not ‘the usual hideous “Jack”‘ but a yellow fairy. One Noah’s Ark had an Egyptian theme.

After the end of the war, arts and crafts exhibitions became an important sales channel, held in many of the major cities around the country throughout the year. In October 1920, they were up in Manchester for a two-day exhibition in Houldsworth Hall. A month later they were touting their wares at a well-received stand at ‘The Childhood Exhibition and Toy Fair’, held at Devonshire House.

In 1922, Louise left to focus on her drawing and painting and Mary teamed up with a new, much younger, partner, Aileen Blanche Ellis (1892-1970). Aileen had trained as a sculptor and during the First World War had made scientific instruments. Now she applied those skills to making skipping ropes and hobby horses.

The women wanted their toys to be both attractive and educational. A weather vane has a Polar bear at the north, a kangaroo hopping south, an elephant looking east and a bison to the West.

At the Daily Mirror Fashion Fair, held in Holland Park Hall in April 1923, they exhibited alongside Jean Patou, Lucy Duff Gordon’s protege Molyneux and perfumiers Roger and Gallet. Six months later they were in Oxford and from then on they were regular participants in a number of large arts and crafts exhibitions. They had a second site on Gunter Grove where the toys were made.

By 1928, according to the Yorkshire Post there were ‘very few well-equipped nurseries nowadays where a Pomona stork or animal of some sort is not to be found.’ However, the Cheyne Walk store did not sell only their work. In the early days, with the war raging, William Wildman made a series of wooden soldiers and sailors, 3 1/2 inches high that they sold for 1 shilling 6 pence each. During the 1920s, they acted as London agents for another artist-turned-toymaker, Mary Baylis Barnard. Based in Oban, by the mid-1920s she was employing four more women to keep the stock flowing into her Bunny Shop. She had met her husband, Duncan, also an artist, when they were both studying at the Académie Delécleuse, undoubtedly how the two Marys knew one another and yet another example of women using their networks to progress commercial ventures.

The 1920 Manchester exhibition where Pomona Toys had exhibited was an initiative of the Red Rose Guild, composed of northern artist and craftspeople living in London. One was the artist Dorothy Hutton. The success of this first exhibition led to the creation of the Red Rose Guild of Artworkers in January 1921. Mary became a member and the Manchester show became an annual event, attracting lots of press coverage.

In 1927, Mary and Aileen moved their store to 14 Holland Street, just off Kensington High Street. Four years earlier, Dorothy Hutton had opened the Three Shields Gallery just along the street at number 8. As well as displaying her own work Dorothy held regular exhibitions showcasing the work of other craftspeople, including the now-renowned hand-weaver Ethel Mairet (1872-1952), another Red Rose Guild member.

Through the 1930s, the pair continued to innovate. They developed a ‘Make Your Own Animals’ set with colours, thin wood and a fret-saw for the use of a ‘neat-handed child’. Their ‘nailing set’ meant children could wield a hammer to turn triangles, circles and ovals into ships, windmills and trees. Parents of a nervous disposition could still opt for low-risk toys such as a winter sports scene, complete with skiers on the cotton-wool snow and miniature skaters on the looking-glass lake.

There is little news about the company after 1936 and it seems to have folded when the war broke out in 1939. By then Mary was 71. She died eight years later and was buried in Brompton Cemetery. The centenary of Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House this year is a great excuse to re-visit her many achievements.

Two more Pomona Toys from the Dolls’ House (c) Royal Collections Trust

With thanks to the team at the Heath Robinson Museum, whose recent exhibition on Mary Wheelhouse prompted this entry and provided a lot of useful material.

For a comprehensive set of images of Pomona Toys, you can read this article by Rebecca Green from 2010.

Other sources include:

The Graphic 18/12/1915; The Bystander 6/12/1916; Pall Mall Gazette 19/11/1920; Daily Mirror 13/12/1922; Oxfordshire Weekly News 31/10/1923; Oban Times and Argyllshire Advertiser 26/9/1926; Yorkshire Post 15/11/1928; Birmingham Post 25/1/1933; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 19/10/1934