Sector: Construction

She designed buildings and built communities

At least once a week I drive from my home to Hampstead Heath to walk my dog. As I navigate around Swiss Cottage, I find myself glancing left towards a shopping arcade, hemmed in by the A41, not because of its beauty but because I know it was designed by Gertrude Leverkus, one of the first women to practise as an architect in Britain.

There are traces of Gertrude Leverkus’s work all over London and beyond. She had a forty-year career during which she worked on a range of domestic and corporate projects, most notably the development of the new town of Crawley. As architect to Women’s Pioneer Housing, still thriving today, she helped provide working women in London with affordable accommodation. But her legacy goes well beyond any physical structures that survive: she worked hard to encourage other women to become architects and volunteered for a wide range of organisations.

Gertrude was born on 26th September 1898 in Oldenburg, her parents’ home town, near Bremen. Her father, Otto, had emigrated to Manchester two decades earlier and become a British citizen. On his marriage in 1881, his wife Rosalia joined him in Britain and they had two children, William and Elsie. Otto’s work meant that many of the following years were spent living in Spain but by the time Gertrude was born in 1898, fifteen years after Elsie, the family was about to return to Britain.

For the first seven years of her life, Gertrude lived in Forest Hill and it was here that her younger sister Dorothy, known as Dolly, was born eighteen months after Gertrude. Forest Hill was home to one of the biggest German communities in London, attracting wealthy merchants who were expanding their businesses in Britain. A German evangelical church was built there in 1883.

When Gertrude was about eight years old the family moved back up to Manchester. Elsie trained at Manchester School of Art and it was her desire to pursue a career as an artist that triggered the next move back down south to Bushey. Elsie studied at the art school that was established by Herman Herkomer and taken on in 1904 by one of his star students, Lucy Kemp-Welch. (Another one of Elsie’s art tutors was Percyval Tudor-Hart whose daughter-in-law, Edith, was a noted documentary photographer and a Russian spy).

It is clear from the support Elsie was given that Gertrude’s parents were serious about their daughters’ education. While the family was living in Bushey, Gertrude attended Corran School in Watford, co-founded by Eleanor Jourdain, later principal of St Hugh’s College, Oxford. When the family moved back to Forest Hill, Gertrude and Dolly went to Sydenham High School, one of the last schools to be set up by the Girls Day School Trust.

While Dolly chose a career in medicine, Gertrude’s father encouraged her into architecture. She was smart and liked drawing so when in 1915, he saw a letter by a woman in a newspaper saying that women could now be architects he thought this could be where her future lay.

Enjoying this story? Subscribe to my newsletter or follow me on instagram to find out more about pioneering business women and their networks, as well as relevant exhibitions, talks, books and events.

Women in architecture

Architecture at this point was a career that was semi-open to women. In the early 1890s Ethel Charles (1871-1962) and her sister Bessie were the first to embark on a route to qualification. The Architectural Association, the oldest independent school of architecture in the country, refused their application to study there and so they trained in an architect’s office. They were also excluded from the professional elements of the architecture degree at UCL but attended some of the other modules that were part of the course. By cobbling together their own programme of academic and practical education, they were in a position to sit the associates’ exam at RIBA, the Royal Institution of British Architects. Ethel went first, passing in 1898 and after a lot of opposition she was accepted as an associate member. Bessie followed in her footsteps two years’ later. Elspeth Mclelland (1879-1920) studied at the Polytechnic Architectural School and from there started designing houses.

Gertrude was encouraged by her father to attend a series of lectures on Gothic Architecture at the South Kensington Museum (later the V&A). She asked the lecturer for some careers advice and he put her in touch with another woman, Annie Hall, who had followed a similar path to the Charles sisters, training under Thomas Overbury, a Cheltenham-based architect. In 1912 Annie was the first woman to be accepted as member of the Society of Architects and set up her own practice at 5 Verulan Buildings in Gray’s Inn. She suggested that Gertrude study at University College London (UCL).

UCL had recently opened a purpose-built School of Architecture and blazed a trail by admitting women to its undergraduate course. The syllabus included studio work, the history of architecture, German, mathematics and Latin and Roman history. When Gertrude started in 1915, there were two women in the year above her and three in her own year. She was the only one of the five to complete the course and became the first woman to graduate in 1918.

In 1922, after a gap of more than twenty years, RIBA finally accepted three more women as associate members: Gertrude, along with Eleanor KD Hughes; and Winifred Ryle (later Maddock), who had both studied at the AA, which opened to women in 1917. These admissions marked ‘a step forward in the rather slow progress of the woman architect’, according to The Times. Three soon became four when they were joined by Gillian Cooke, later Harrison, another AA graduate.

Women’s Pioneer Housing (WPH)

After Gertrude graduated, she was introduced to Horace Field, an architect who had done some of his training under Olive Edis‘s uncle, Robert William Edis. Through his wife’s friendship with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Field was the consulting architect on the New Hospital for Women and Gertrude also did some work for the Garrett Anderson family in Aldeburgh. Gertrude’s first projects were all houses, often commissioned by women, including the artist Sybil Maude. She also designed a new family home in Harrow for her, her sisters and mother, the first one they had owned. However, her most significant client during this period was Women’s Pioneer Housing.

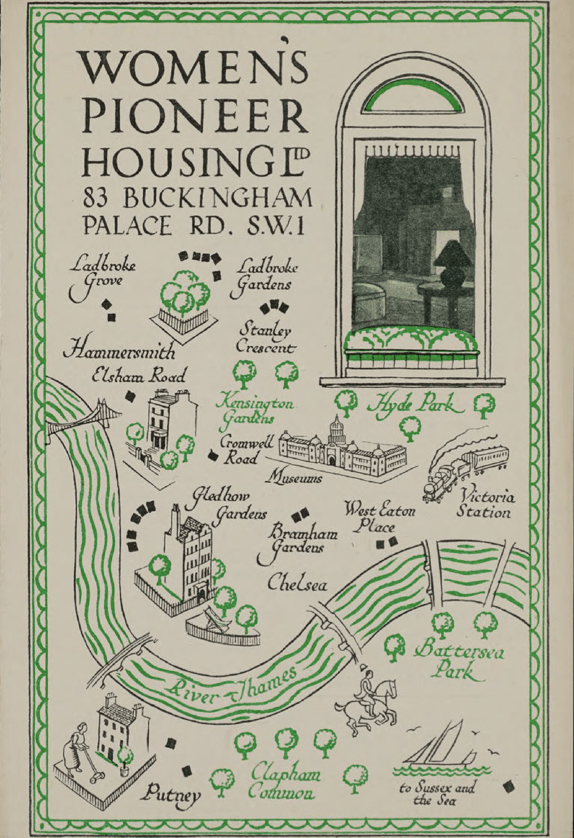

Founded by Etheldred Browning, an Anglo-Irish suffragette, in 1920, Women’s Pioneer Housing described itself as ‘the first women’s Public Utility Society’.

It was a social enterprise providing affordable housing for single women in London, particularly working women. Finding affordable housing had long been a challenge for women who wanted to work in London and were unable or unwilling to live at home but with around 1.5m ‘surplus women’ needing to support themselves after the First World War, the need was now even more acute.

WPH bought large London houses in good residential neighbourhoods that were now too big for one family and converted them into bed-sits and small flats. Gertrude undertook her first project from them in 1923, converting 62 Ladbroke Grove into eight flats. The following year she was officially appointed as the organisation’s architect. Gertrude was clearly kept very busy. Between 1925 and 1935, the number of houses managed by the WPH increased from 15 to 55 and the number of flats grew from 109 to 522. One project was the conversion of 65 Harrington Gardens and it was here that Gertrude rented rooms and lived until her retirement.

The organisation and its mainly-female team attracted a lot of attention. ‘It is frequently said that women cannot manage intricate financial business’, said one newspaper in 1931. ‘One housing corporation has set up a unique record which shatters this illusion.’ By then as well as Etheldred and Gertrude, the organisation had Ethel Watts as its accountant and nine women on the management committee. High-profile names who sat on the committee at various times included Lady Shelley Rolls, Lady Rhondda, Constance Peel and Ray Strachey and among the shareholders was Nancy Astor.

Etheldred introduced Gertrude to the Women’s Provisional Club (WPC) and she became of its longest-serving members, still attending its events fifty years later. Helen Archdale, the first Chair of the Committee of Management and another WPC member, was a close friend of Lady Rhondda and in 1925 they moved into ‘Stonepitts’ in Kemsing, Kent. Gertrude designed an elaborate drainage scheme for the house and made certain internal alterations while another Gertrude, Gertrude Jekyll laid out the garden.

The 1930s

When Horace Field retired in the late 1920s, he gave Gertrude all his drawings and office effects and went with his wife Mary to live in Rye in a house Gertrude had altered for them. She remained in the same office, 5 Gower Street, opposite no. 2, the home of Agnes Garrett and Millicent Fawcett. In the early 1930s she invited Eleanor Hughes to join her as an independent architect. As well as her ongoing work for Women’s Pioneer Housing, Gertrude designed and built a new ante-natal department for the Annie McCall Maternity Hospital in Clapham.

Gertrude was an advocate for architecture as a career for women. In 1928, she spoke at a careers event organised by the Union of Women Voters alongside Laura Annie Willson, who shared her experience of building houses, and fellow WPC members Ethel Wood, Caroline Haslett and Gladys Burlton. In December 1931, Gertrude was among 29 new Fellows of RIBA elected, making her the second woman allowed to put the initials FRIBA after her name. (Gillian Harrison was the first, elected a few weeks earlier.) Gertrude soon formed a Women’s Committee so women had somewhere to discuss their experiences and increase their visibility. She helped organise an exhibition of women’s work at the RIBA offices and spoke about women’s professional successes.

One particularly notable adventure came in the summer of 1938. The husband of one of her long-standing friends was the British Consul General for the province of Khorasan and Gertrude escorted their daughter out to see them after school term ended. It was a long but exciting trip: the Orient Express to Istanbul, a ferry across the Bosphorus then on to Mosul via Ankara and Damascus. From Mosul a Rolls Royce took them to Kirkuk, then there was another train to the Persian border and a three-day journey to Mashhad via Tehran. After a journey like that, it is not surprising that Gertrude stayed for over three months before doing the journey in reverse to return her friend’s daughter to school. She might have been on holiday but she was not idle: she designed and supervised the building of an open-air swimming pool and designed a new bungalow for the Vice Consul.

The war years

When war broke out, Gertrude got to work installing air raid shelters in the WPH’s buildings. One of the students in the year ahead of her at UCL was Clare Nauheim. She spent some time working with Edwin Lutyens and then in 1933 married the industrialist Harry Railing. Clare recruited Gertrude to work for the Women’s Voluntary Service so she ended her Gower Street lease, stored her office furniture and started working as the centre organiser for the borough of Holborn. The team there found accommodation for refugees, gathered clothing, made up beds in shelters and collected aluminium. Gertrude was also Chair of the Publicity Sub-Committee, running themed fund-raising drives such as Weapons Week, Warship Week and Wings for Victory Week, drumming up donations through advertising campaigns and auctions.

She vividly recalled a meeting of the Women’s Home Defence in the Holborn Restaurant in 1942 where Dame Helen Gwynne-Vaughan and Dr Edith Summerskill suggested they learned how to shoot and doled out no-brainer advice. In the event of an invasion ‘we were told that if a German invader were to ask us where was Buckingham Palace, we were of course to point them in the opposite direction.’

New towns, new opportunities

Soon, however, Gertrude’s professional skills were needed as the relentless bomb damage meant extensive re-building projects. In 1925 Gertrude had studied for and been awarded a certificate in town planning and in 1943 she was able to put it to use when she was appointed as a housing architect in West Ham’s Architect and Town Planning Officer’s department. She worked there for five years, developing re-construction projects and taking part in lively debates about the importance of thoughtful design and the need for recreational spaces.

When management changes brought her job there to a sudden end, Gertrude quickly found a position at Norman and Dawburn, a practice based, by a weird coincidence, at Gertrude’s former offices at 5 Gower Street. Here the projects she took on were larger in scale. She worked on corporate head offices and smaller re-development schemes including one at Swiss Cottage, for which she designed a shopping parade which still stands today, hemmed in by the expanded A41. She was also able to put into practice her ideas for satellite towns. Determined to ensure Britain’s towns did not keep sprawling ever outwards, the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act make it easier to create greenbelts around cities like London, with new towns built beyond them. One of these was Crawley and Gertrude designed 735 houses in Pound Hill, the largest of Crawley’s fourteen neighbourhoods.

Gertrude’s life in post-war London was not just filled with work. She had always enjoyed drama, joining UCL’s college dramatic society when she was first a student and later the RIBA drama society. Now she took up acting again and made regular trips to the theatre. To keep her knowledge fresh she took courses at the City Lit.

Norman and Dawburn was extremely successful, outgrowing its Gower Street office and then their next location in Tottenham Court Road before taking over five floors in Portland Place for their 100 staff. By the time she retired in 1960 Gertrude was an Associate Partner, taking a percentage of the annual profits and running her own team. She moved down to Brighton which became her final home town. Ever active, she joined the Regency Society, the Archaeological Society and the British Federation of University Women (BFUW) and was a governor of the Brixton School of Building.

Gertrude died in 1989 but her name and her work live on. She was one of the women featured on 2022’s City of Women London map, with West Ham station re-named in her honour; and the Women’s Pioneer Society is still running over 100 years later. Today around 29% of architects are women overall but what Gertrude would probably be most pleased about is that the gender split among architects under the age of 30 is nearer 50:50.

The website of the Women’s Pioneer Housing has a wealth of information about its history, its management and its tenants.

The LSE Women’s Library holds Gertrude Leverkus’s autobiographical writings.

Other sources include:

The Queen 17/1/1912; The Vote 19/12/1919; The Vote 11/3/1921; The Times 18/12/1922; Daily Telegraph 9/5/1928; The Sunday Sun 1/11/1931: The Scotsman 7/12/1931;