Born: Florence Annie Rowe; also known as Lady Boot, Baroness Trent of Nottingham

Sector: Retail

On Monday 24th September 1917, Boots held its ordinary general meeting at the Midland Grand Hotel in London. One of the board directors had recently died and the chairman and founder of the company, Sir Jesse Boot, had a proposal for who should fill the gap: his wife, Florence.

He was quick to head off any accusations of nepotism: ‘Lady Boot has a long business experience which few women of the time can claim to equal’. Four years early, The Bystander magazine had agreed with him, writing that, due to Jesse’s poor health ‘it is in Lady Boot’s hands that the bulk of the administrative work now rests. Lady Boot is, perhaps, the most wonderful example of the modern business woman in England’.

The Bystander might have been right about Florence’s status among other business women but her role was far more than administrative and was not simply a consequence of her husband’s ill-health. She had been shaping and growing the Boots brand for thirty years.

Florence was born in 29th July 1863 in St Helier on the isle of Jersey, the second of three daughters. She had a strong role model in her mother who worked alongside her father in their bookselling and stationary business. ‘I can never remember the time I was not in [a shop]’, Florence later wrote and her earliest memories were of ‘toddling round the counters at my father’s side and learning from him that all labour was dignified..and that life in a shop could be and out to be a high calling.’ She left school at 14 and became a full-time assistant in the shop. Sociable and bubbly, she enjoyed engaging with and helping customers and was clearly commercially astute.

Marriage and children

In 1885, Florence met Jesse Boot, who was 35. Born in Nottingham, his father died when he was ten. His mother was left to run the herbalist shop that they had set up together and at the age of 13 Jesse had to leave school to help her. When the revenue from their proprietary herbal drugs started to be affected by the rise of branded, patent medicines, widely publicised through well-funded advertising campaigns, a change was needed. In 1877 Jesse took sole control of the business and decided on a bold new strategy. He started selling branded products at low prices, relying on high volumes to offset the low margins. His approach was hugely successful and he invested the profits in developing and making new proprietary lines where he had more control of the margins. At the same time, he expanded the retail network to drive more revenue. In 1883 Boots became a limited company, enabling him to employ qualified pharmacists and dispense medicines.

He might have been financially successful but it came at the cost of his health. In 1885, suffering from burnout and depression, Jesse took a break and went to Jersey to recuperate. This is where he met Florence, possibly at church. They were married in St Helier on 30th August 1886, a month after Florence’s 23rd birthday.

Florence’s mother was apparently so unhappy at this match that she didn’t attend the wedding but her disapproval clearly had no effect on her daughter’s decision.

Make up and magazines

Florence might have been 13 years younger than Jesse but they were equals at work and her gregariousness balanced out his more reserved nature. One of the first things she did was to persuade him to expand the Boots product range beyond pills and potions. She established what became known as no. 2 department, which sold beauty products and gifts, books and magazines, art supplies and picture frames. Boots became more like a small high-street department store than a pharmacy or chemist.

In 1889, Florence and Jesse had a son, John, the first of their three children. However, Florence kept on working, taking John to work in his carry cot and feeding him in the office. John was quickly followed by two daughters and when they were small, rather than their father coming home to join them to lunch, Florence took them to the office and discussed business policy with him while they all ate together.

One innovation the couple collaborated on was a new stationery offer. Jesse had decided to set up a new in-house printing department and Florence developed an in-house product range, applying her insight from her years working in her father’s shop. In 1895 Boots started publishing its annual scribbling diary, branded and sold at cost price as a form of advertising.

Once the children were slightly older, she made buying trips to Germany and France and visited New York twice. She did a full working week, making visits to branches every week and oversaw the recruitment of all members of staff for her department.

Leisurely shopping

Florence had a keen interest in interior design and layout, all with a view to increasing sales. In 1892 she played a major role in the design of Boots’ flagship store on Pelham Street in Nottingham, which was the template for the rest of the chain, and had heated debates with Jesse about where to position product lines to drive revenue.

She wanted the discretionary purchases like toiletries at the front, so customers had to walk past them to get to the essential pharmaceutical products at the back, while Jesse wanted the dispensing counter at the front. In the end she forced a compromise, claiming valuable counter space for her cosmetics. She also introduced cafés to some of the larger stores, choosing the décor, furnishings, tableware and menus.

Florence’s most significant innovation was the launch of Mrs Boot’s Book Lovers’ Library in 1898. She had seen something similar on a trip to the US and realised how the cycle of borrowing and returning books could keep customers coming back to the store and noticing new things to buy. By 1903 there were libraries in 193 branches and during its heyday in the mid-1930s there were 450 with over half a million subscribers and book loans of 35 million.

However, their early success triggered a decision by Florence that would prove to be much more controversial.

University girls

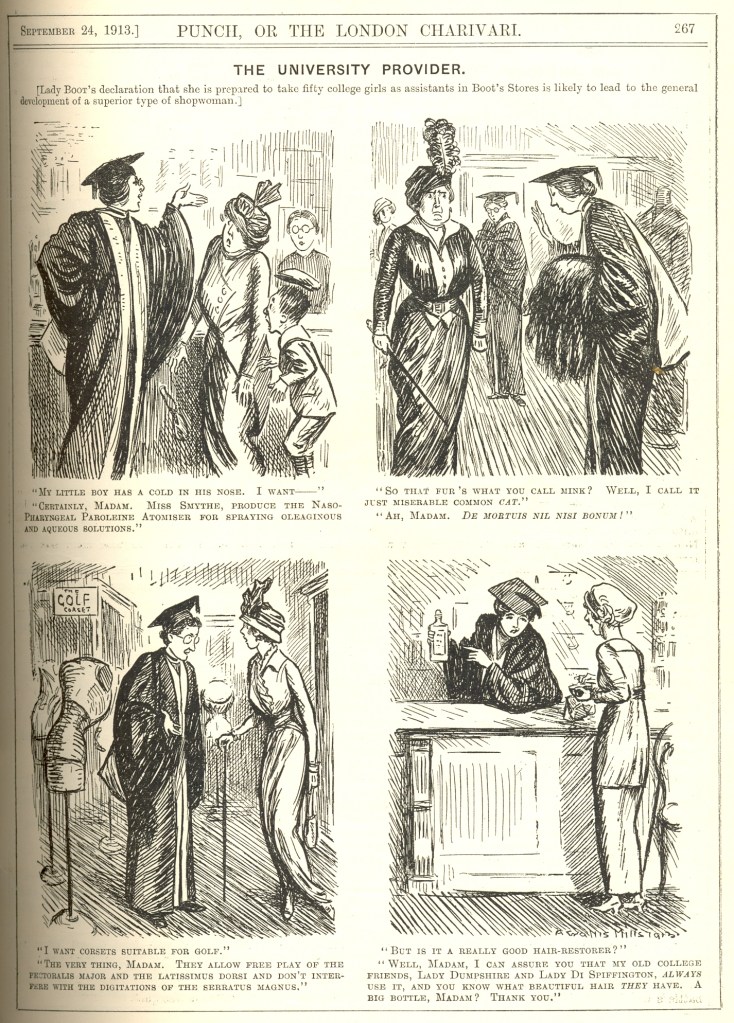

Women began studying at university in Britain in the late 1860s. Graduates in the late 1800s and early 1900s who chose to pursue a commercial career after this were generally treated with suspicion. Surely these women should be going into teaching, not making commercial decisions? Was the world of commerce really the place for a well-educated woman?

On 15th September 1913, the Daily Mail published a letter from Florence offering to take and train fifty women graduates who she felt were needed in the business world because of their ‘superior training’. She proposed a ‘fast-track’ training scheme so that within a year the could be heads of departments, managing teams of women. While men who graduated were heading into the Civil Service, women should enter the retail sector. It was one of the biggest sectors in the country and ‘the high branches of it have as much need for special training as the service of the State.’

By now she was Lady Boot. Both she and her husband were supporters of the Liberal Party and Jesse had been knighted in 1909, early in Asquith’s term as Prime Minister. The following year the spotlight had briefly shone on Florence when she founded a new Liberal women’s group, the Marguerite League, to attract more women to the Liberal cause and spread Liberal principles. It was a response to the well-established Primrose League of the Conservatives and Florence undoubtedly had a hand in the ‘beautifully-designed’ brooches in the shape the head of a daisy given to members. However, after the initial surge of excitement, the League seems to have faded away, with no mention of it in the press after that first year.

Her announcement in 1913 put Lady Boot back in the spotlight. It sparked plenty of public comment and a loud rebellion from Boots employees and almost immediately another letter was needed, this time to the ‘hundreds of young women’ employed by the firm. She reassured them that this recruitment decision would have no bearing on their jobs or their pay but it was not enough to quieten all the noise. The local branch of the Clerks’ Union tabled a motion two months later, criticising Florence’s idea and reminding Jesse that his loyalties should lie with the working classes: they made up the bulk of both his customers and college girls had no right to take the jobs of their daughters.

Jesse Boot objected, pointing out that graduates would mainly be employed in the lending libraries ‘for which we require girls of exceptional training’. There were still plenty of career opportunities for girls from higher grade or secondary schools in the no.2 departments and he had consistently shown how serious he was about developing his staff through a range of educational initiatives that were open to all.

The proposer of the motion could find no seconder and the issue faded away. In the end Florence fell well short of her recruitment target but it brought to light an issue that persisted well into the 1920s. In late 1925, Lady Rhondda set up the Business and University Committee to address head on perceptions that there was no room in business for a girl with a degree.

Getting on board

Through business partnerships and a chain of acquisitions, the number of Boots stores grew rapidly, reaching 251 by 1901 and more than doubling to 560 by 1914.

When Jesse appointed Florence to the board in 1917, as well as valuing her role in developing the look, feel and commercial proposition of Boots he felt she brought another important quality to the party: ‘As the staff of the company becomes more and more recruited from women there should be a woman member of the board who has specially sympathy with and knowledge of their wants and feelings’.

Boots was one of the first companies to appoint a full-time welfare officer, Eleanor Kelly, in 1911. Before that, it was Florence who had taken responsibility for women who worked for Boots. From the early days, she took a personal interest in female shop and factory workers, checking in with them on her regular store visits. When she found out that some girls were coming to work without having breakfast she laid on hot cocoa. She often made visits at home to members of staff who were ill. She sent women members of staff a silk banner at Christmas printed with inspirational hymns or lines of poetry.

Florence also arranged staff outings. The first outing recorded in the archives was in 1888, when the staff were taken on a picnic. In 1902 she took 500 girls to the seaside at Skegness and in 1908 organised for nearly 1,000 to travel by train to London to see the Franco-British exhibition at Wembley. She took her responsibilities seriously and would write letters to the parents of the staff members attending the outings, assuring them of the number of chaperons available to watch over the girls, thereby ensuring their safety. This genuine concern for Boots’ employees was another reason why she took so seriously the furore about her decision to hire women graduates.

The fruits of success

Jesse had considered giving up the business at a couple of points but Florence talked him out of it. However, in 1920, ill-health finally forced him to retire. Rather than passing the business on to his son, he sold it for £2.25m. The following year, when their younger daughter, Margery, married, it was Florence who gave her away, Jesse perhaps unable to walk her down the aisle.

During the 1920s they enjoyed their wealth and freedom. In 1923 Jesse bought Florence her own private bay, Beaufort Bay and in 1925 they purchased the Villa Springland, very close to Cannes and famed for its beautiful gardens. There Florence quickly developed a reputation as a generous and hostess, unfazed by the unexpected. When she agreed to host a talk on the new League of Nations in January 1926 it was unexpectedly popular, attracting over 180 people. Florence brought her management skills to bear, organising seating and tea for all of them: ‘Few villas round here could have managed that.’ She threw lots of parties and invited many guests down for longer stays including Margot Asquith, Lady Oxford.

However, much of their time and money was devoted to philanthropic activities. When they moved from Nottingham to Milbrook in Jersey, they built cottages and sporting fields on the island, which were named after Florence.

Their biggest project was the development of University College, Nottingham, which had been founded in 1877 and outgrown its space in the centre of the town. Florence and Jesse donated 35 acres of land so that a new campus could be built and gave money for the construction of the buildings. These included Florence Boot Hall, a purpose-built hall of residence for women students. In 1928 King George V opened the building and in the 1929 New Year’s Honours list Jesse was elevated to the peerage, making Florence Baroness Trent of Nottingham.

After Jesse’s death in 1931, Florence continued to devote time and money to projects in Jersey. She refurbished the local village church, St Matthew’s at Milbrook in his memory. A neighbour in the South of France had been René Lalique. Florence loved his work and had commissioned him to make interior doors for Villa Springland. Now she chose him to create the stunning interiors. She turned the gardens of Villa Milbrook into a public park, opened in 1936 to coincide with the coronation of George VI. Two years before her death, on 17th June 1952, Beaufort Bay was gifted back to the island.

There is no question of the significance of Florence’s role in the growth of a brand still seen on our high streets, in stations and in shopping centres across the country. So, next time you see the Boots logo, think of this pioneering woman who contributed so much to its success.

I am hugely grateful to Sophie Clapp, Archivist for Boots for sharing her comprehensive research on Florence Boot and sharing these images from the company archives. The Walgreen Boots Alliance Archives has over 500,000 items chronicling the long history of Boots. With lot of digital content it is a valuable resource for anyone researching retail or wider social history.

Other sources include:

Nottingham Daily Express 21/2/1913; Cambridge Independent Press 19/9/1913; Yorkshire Evening Post 2/10/1913; The Bystander 3/12/1913; Nottingham Evening Post 4/12/1913; Western Mail 28/9/1917; John Bull 6/10/1917; The Bystander 26/1/1921; 25/2/1925; 27/1/1926; The Nottingham Journal 9/2/1927; Illustrated London News 31/7/1948; The Times 9/9/2005