Sector: Media

‘Broadcasting is a post-war development and the B.B.C. a post-war institution, with a largely post-war staff. Perhaps this helps to account for the general open-mindedness and tolerance which on the whole prevail, and which one hopes find some reflection in programme building and administration alike. …The organisation has set an example which is not always to be found among public bodies. Women are not compelled to resign on marriage and equal pay for equal work is on the whole respected.’

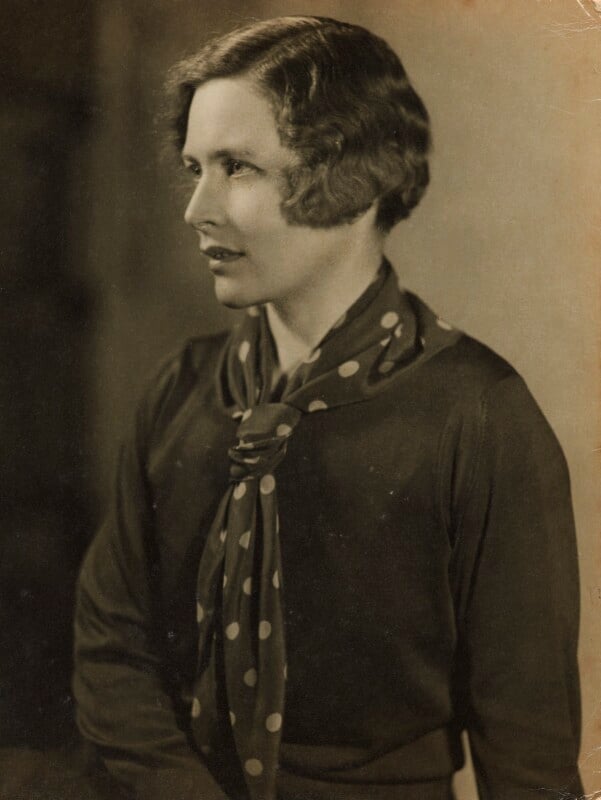

So wrote Hilda Matheson in January 1931. As the BBC’s Director of Talks she was at that point one of the most influential figures in broadcasting, in charge of a department whose influence can still be felt today and earning £1,050 a year. Ten months later, she was out. In her five years at the BBC she laid the foundations for its news and spoken word programming and her impact can still be felt today.

(c) National Portrait Gallery

The UK’s first radio broadcast was more than three decades in the future when Hilda Matheson was born in on 7th June 1888. She grew up in Putney, where her Scottish father was a Presbyterian vicar and her mother occupied herself with parish work. She had a good education thanks to some family money that supplemented her father’s income, but it was slightly truncated by his poor mental health. He took a six-month leave of absence from his ministry in 1904 and Hilda left school at 17 to travel to Europe with her parents and younger brother. Six months became two years and when Hilda finally returned to the UK she was fluent in Italian and German.

Despite the disruption to her final school years, Hilda passed the entrance exams for Oxford University and started to study History in the autumn of 1908, aged 20. Her father had secured a position as chaplain to the University’s Presbyterian students and so Hilda lived at home. Since she didn’t need the accommodation provided by Somerville Hall and Lady Margaret Hall, Hilda joined the Society of Home Students, later St. Anne’s College, which offered academic support for students living locally. She fitted her studies around hockey, acting and singing. While men courted her, her passions were always reserved for women.

When she completed her studies, Hilda stayed in Oxford. She worked as a part-time secretary to the historian H.A.L Fisher, husband of her tutor and mentor, Lettice Fisher then became by an assistant at the Ashmolean Museum under Dr David Hogarth, brother of Janet Hogarth but her stint there was cut short by the war. She served as a VAD and then in 1916 joined the War Office as a clerk. In August she moved into its Special Intelligence Directorate, later to be known as MI5. Although her exact duties are not known, she was probably tasked with identifying and keeping tabs on possible German spies, recording information in a huge card index. Later that year she went out to Rome to help set up a similar operation there, before returning to London in 1918 to head an important section of the main registry. Her contribution was publicly recognised when the war was over.

In October 1919, Nancy Astor became the first woman to take a seat in Parliament after winning a by-election. She needed a political secretary to draft speeches, promote and lobby for her ideas, deal with mountains of correspondence and organise her diary. She was probably introduced to Hilda via mutual friends who had first-hand experience of Hilda’s bright mind and all-round competence, either the Fishers or Philip Kerr, Lloyd George’s private secretary for whom Hilda had also done some work. It was a successful arrangement and over the next five years Hilda provided invaluable support to Lady Astor and worked with Caroline Haslett to secure Astor’s involvement in the International Conference of Women in Science, Industry and Commerce in 1925. Through her management of Astor’s correspondence, diary and event schedule, she built an impressive network spanning London’s political and cultural scenes and crossed paths with John Reith and

John Reith was put in charge of the BBC when it launched in 1922. He saw potential for Hilda in the new sector of broadcasting. By the time he persuaded Hilda to join in September 1926, as an Education Assistant, two million households had licences and the offices on Savoy Hill just off the Strand were becoming increasingly crowded. The organisation was also about to go through a significant change.

The honeymoon period

At the start of 1927, the British Broadcasting Company became the British Broadcasting Corporation. This one-word change signalled its change in status from a commercial organisation, owned by radio companies, to a public corporation financed by a licence fee and governed by a Charter laying out its responsibilities and putting strict limitations on what could be broadcast. Reith immediately re-organised, creating a new Talks Department with Hilda as the Director. Her remit covered all the spoken word programmes apart from drama and children’s programming, so included News, Talks, Politics and Adult Education. With the expanded scope came a pay rise, from £600 to £700 per annum.

It is hard to imagine the BBC as it was then. Listeners had access to one national and one local channel. Programmes were broadcast for seven hours a day and the rest of the time there was silence. 60% of the airtime was allocated to music, with drama, talks and the news filling the remaining hours. News content, which took up only 4% of the schedule, was provided by Reuters and the evening news broadcast was made at 7pm to protect newspaper sales. One of Hilda’s most significant and long-lasting changes was replacing the news feed from Reuters with a bulletin fully edited by BBC staff and during her period in charge, the time devoted to news more than doubled to nearly 10%.

Women made up a third of the workforce, although they were mainly in administrative and junior roles. Internal directives made explicit references to women and men in salaried roles being treated equally when it came to promotion (though whether this happened in practice is debatable) and while pay was not equal, as Hilda said in her 1931 article, women’s salaries were relatively high at the BBC compared to other organisations, with Hilda one of the best-paid. She was also given a lot of latitude and delighted in being unconventional, bringing her dog to work and holding meetings sitting on the floor around the fire.

The Matheson philosophy

According to Richard (R.S.) Lambert, editor of the BBC’s weekly magazine, The Listener, Hilda was ‘enterprising, indefatigable and liberal-minded..she had a sympathetic personality..[and]..visions of the future possibilities of broadcasting, both in the cultural, the political and the entertainment fields.’

She thought hard about her listeners, the people who were at home all day with the radio for company. Writing for Common Cause in 1931, she explained that:

‘Broadcasting can, I think, render quite special services to everyone whose life is in any way circumscribed by isolation, ill-health, age, lack of leisure or lack of means. And for the majority of women whose active lives centre on their own homes, broadcasting can be used, and is being used, not only as a means of getting practical help on everyday problems, but also as a link with outside interests, persons and things, to a degree never yet experienced by them.’

She would echo these sentiments in her 1933 book ‘Broadcasting’: ‘

It is difficult to exaggerate what broadcasting has done for women. The world at large stands to gain much from the wider outlook, greater interest and more up-to-date practical knowledge which wireless has brought into their homes.’

She brought women’s voices into the evening talks schedule and re-instated specific talks aimed at women, experimenting with form and timing. One early contributor to Household Talks was the head of the Good Housekeeping Institute, Dorothy Cottington Taylor, who shared advice on jam-making, spring cleaning and how to make a Christmas cake. Women were given their due status as experts and pioneers in areas including occupational psychology, children’s development and education and women’s health. When the Equal Franchise Act was passed in 1928, she kicked off a series of programmes to discuss some of the public and social questions women might be interested in, in the run up to the next election, whenever that might be. Topics explored included ‘Should Women Earn As Much As Men?’, ‘Should Married Women Work?’ and ‘Should Wages Be Supplemented by Family Allowances?’

She was determined to make talks sound personal and relatable, scripted so they were well-structured but sounded spontaneous, with the speaker using more informal language: ‘won’t’ rather than ‘will not’, for example. She was well aware of the inherent challenge of ensuring free speech and the expression of minority opinions on the one hand while facing the practical challenge of having all shades of opinions represented. One of her innovations to make politics accessible, ‘The Week in Westminster’, is still running.

Work tensions

In June 1929, Hilda wrote in a letter that ‘I am happier than anyone could believe possible.. I have an ideal job and a very good screw (salary) and nice people to work with.’

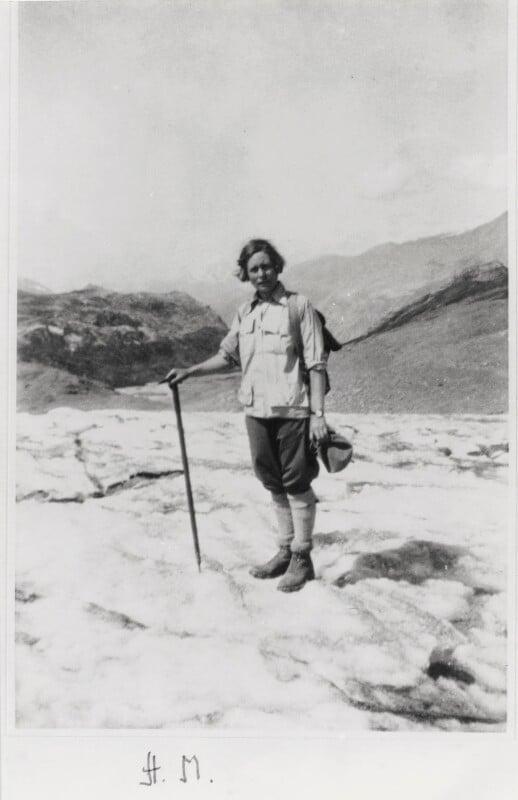

The recipient was Vita Sackville-West. The two women had met in the summer of 1928 and had started to grow close. In December 1928 Hilda invited the her to discuss ‘The Modern Woman’ with Hugh Walpole and immediately after the broadcast she and Vita embarked on a passionate two-year affair. By Christmas that year, Vita had already written Hilda fifty letters; Hilda was, if anything, even more enthusiastic. She was also much less reluctant than Vita, married with two children, to hide their affair but complied with Vita’s desire for discretion. They holidayed together in Val d’Isère in July and Hilda helped Vita find a London flat in the Inner Temple, at 4 King’s Bench Walk.

print, circa 1927

(c) National Portrait Gallery

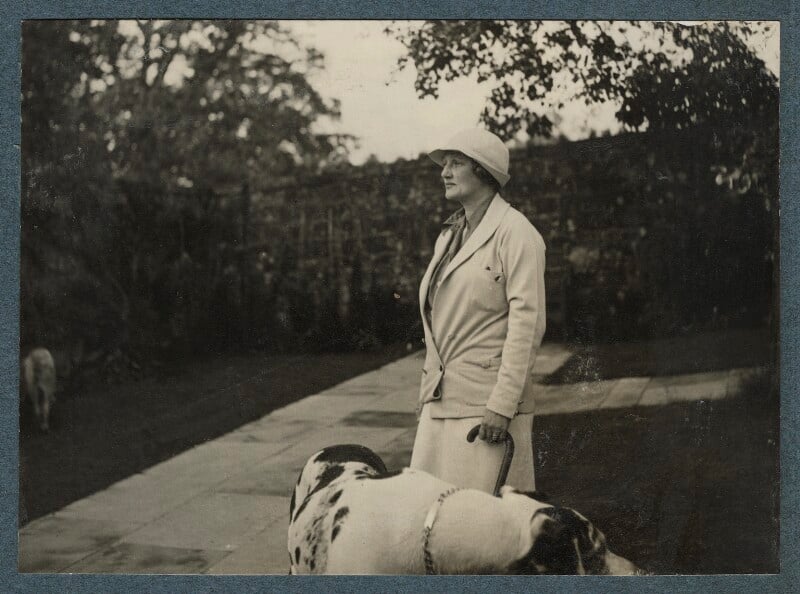

bromide print (c) National Portrait Gallery

Hilda gave Vita’s career a boost, with a regular weekly slot reviewing fiction and Harold also became a regularly-heard voice, fronting a series on ‘People and Things’.

As Hilda became more embroiled with Vita and the Nicolson’s new project to restore the derelict castle they had bought in Sissinghurst, her commitment to tackling knotty issues on air was starting to cause ructions at work. In January 1929, she arranged the first live debate between the Liberal, Labour and Conservative parties, seventy minutes of discussion on the De-Rating Act, which was intended to encourage agriculture and industry by freeing them from a portion of the rates. It was deemed a huge success and gave Hilda the confidence to push harder for Talks to embrace more controversial topics. Reith was not convinced and he was the one with the power.

In October 1929, he re-organised, folding the Adult Education (Talks) department into the Talks (General) department while hiving off, ‘Topicality’ or Outside Broadcasts and News, an area Hilda particularly enjoyed, into a new department. Charles Siepmann, the head of Adult Education was left in place and reported to Hilda.

As Hilda pursued her agenda, her relationship with Reith deteriorated further. In March 1930, Reith recorded in his diary that he was ‘developing a great dislike for Miss Matheson and all her works’. In early 1931 he made more changes: Talks and Adult Education were split out into two separate teams, with Hilda and Charles now peers. The final straw came in the autumn of that year. Hilda had commissioned a series of talks from Harold Nicolson, Vita’s husband, on The New Spirit in Literature but he was told that he could not mention either D.H. Lawrence or James Joyce. A compromise was reached but Hilda had had enough and in October she tendered her resignation. ‘And so the B.B.C.lost its most single-minded, progressive and humane Talks Director who had created the Department and placed Talks ‘upon the map” of broadcasting.’ With her departure the Talks lost its sense of vitality and experimentation and the degree of censorship increased.

Life post Beeb

On leaving the BBC Hilda embarked on what would now be described as a portfolio career that drew on all of her earlier experience. She had dipped her toe into the world of women’s networks and joined the Women’s Provisional Club in the summer of 1931, but it was clearly not for her and she was only a member for a year. The networks she drew on were her own.

She took over secretarial duties for Vita and her husband, organising speaking tour for Harold Nicolson in the United States. (When Harold was playing with the idea of writing a novel in 1932, he had Hilda in mind as the model for a parliamentary Under-Secretary and indeed wrote her into ‘Public Faces’.) She wrote a book on Broadcasting that was published in 1933, the first one dedicated to this topic. She started writing for a range of publications — when three hundred ‘representative women’ were invited to the BBC to discuss the talks for women she covered the event for The Observer.

In her personal life, Hilda Matheson had a formed a relationship with Dorothy Wellesley, a poet and former lover of Vita’s and moved to live with her near Tunbridge Wells.

Vintage snapshot print, 1935 (c) National Portrait Gallery

Then in July 1933 came the role that would occupy her for the next five years. She was appointed Secretary of the African Research Survey, a five-year project to compile ‘a comparative study of the existing situation and of the methods employed by different powers in Africa’ that could form the basis for co-operation on future developments. With Lord Hailey, the official author of the report, ill for much of the time, she was effectively in charge and did ‘a remarkable job’. When it was published in November 1938, she was awarded an O.B.E. in the New Year’s Honours List.

It was in the course of this job she concluded that the world needed to know more about Britain’s traditions and achievements. She came up with the idea of a series of books to show the world what Britain stood for, what it had done and what is was still doing and pitched it to William Collins. The result was three series of books: ‘Britain in Pictures’; ‘The British Commonwealth in Pictures’; and ‘The English Poets in Pictures’.

When war broke out, Hilda joined the Ministry of Information and set up a Broadcasting Committee, which included her former BBC colleague, Iza Benzie. (When Hilda was done for speeding on 11th April 1940, her solicitor put up a defence that she on Government duty at the time but to no avail: she was still fined 50 shillings.) They focused on publicity work mostly in South America. Perhaps she crossed paths with Margaret Havinden, who as Chair of the Dress Designers’ Committee was organising a South American Exhibition of mannequins sporting designs by the top British couture houses.

However, her war-time contribution was brief. She was diagnosed with Graves disease and did not survive an operation to remove part of her thyroid gland, dying on 30th October 1940.

Career in context

In its first two decades, the B.B.C. was perceived both internally and externally as somewhere women could have a successful career but this was not sustained into the 1950s. In September 1959, the former BBC governor, Mary Agnes Hamilton, wrote to The Times decrying the lack of representation of women in senior roles at the BBC compared to the inter-war years. There are similarities here with advertising, magazine publishing and literary agencies. Like the BBC, they were all in the emergent stage during this period, with few hard-wired policies, processes, structures and hierarchies. As Hilda reflected, this sort of environment was usually to the benefit of women, giving them more influence over their own work, progression and the wider working environment. Organisations need to consider how systemic factors might be influencing their expectations of women before embarking on targeted leadership programmes to ensure they conform.

In 2022, the BBC broadcast a five-part radio series, ‘The Battle of Savoy Hill’, dramatising Hilda’s 1931 battle with John Reith. The episodes are currently unavailable but you can read more about it here.

Sources: Kate Murphy has done extensive research on the contribution of women to the BBC in its early years, published in ‘Behind the Wireless: A History of Early Women at the BBC’ (2016). I have drawn on her work in this post. Michael Carney’s biography of Hilda, originally published in 1999 and re-published in 2023 with additional material by Kate Murphy, has also been invaluable.

Other sources include:

Woman’s Leader and Common Cause 2/1/1931; St. Pancras Gazette 8/12/1933; The Eastern African Standard 10/11/1934; Western Morning News 2/1/1939; The Bystander 31/1/1940; Sevenoaks Chronicle and Kentish Advertiser 17/5/1940; Oban Times and Argyllshire Advertiser 9/11/1940; Bookseller 13/3/1941

‘Broadcasting’ by Hilda Matheson (1933); ‘Ariel and All His Quality’ by Richard S. Lambert (1940)

‘Vita: the life of Vita Sackville-West’ by Victoria Glendinning (1983); ‘The Harold Nicolson Diaries 1907-1964’ (2004) ed. Nigel Nicolson.

What a woman!

LikeLike