Born: Hélène Reinherz

Sector: Retail (Specialized Consumer Services)

My culinary experiences at school in the 1980s were not particularly inspiring. In my first class I had to polish a tomato, cut up some cheese and pour out a glass of milk to make something called ‘the Oslo meal’. In the second I had to draw all the implements in the cutlery drawer. I don’t remember any connection being made between my physics, chemistry and ‘domestic science’ lessons as I scrambled eggs and wondered whether my cake would emerge risen or sunk.

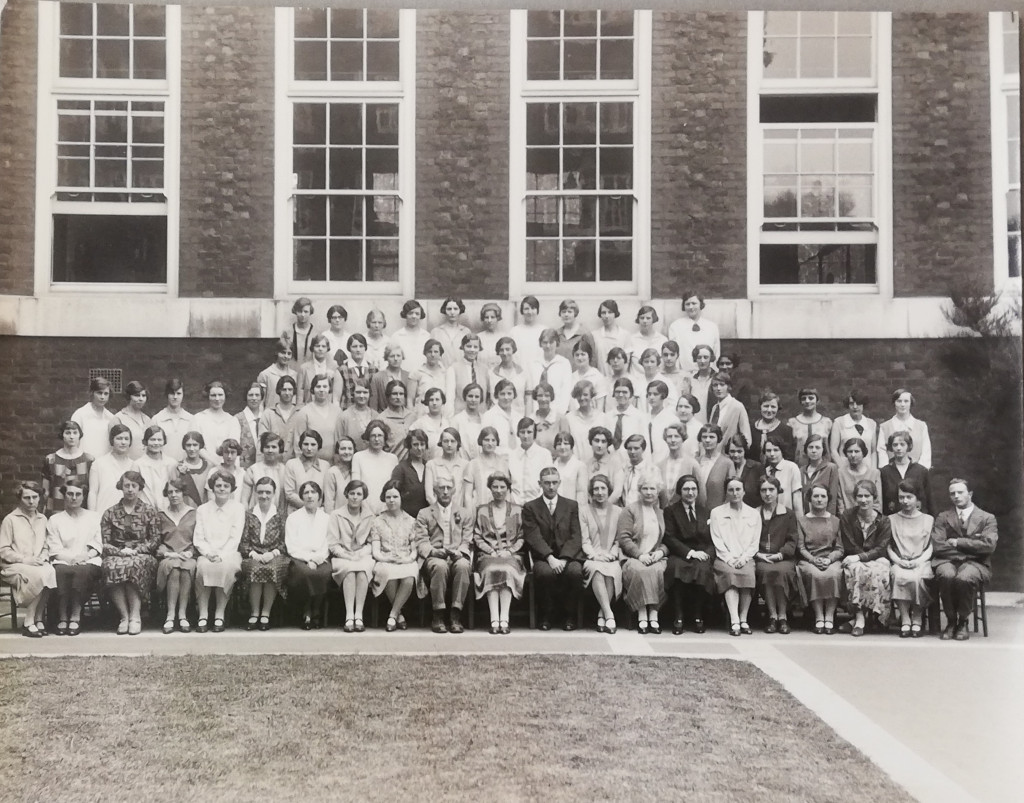

Had Hélène Reynard been watching, she would have been deeply depressed. She spent her career seeking to make domestic science a serious subject that led to respected careers. She brought together the commercial and the academic, the scientific and the practical in management roles. From one angle she is one of the most visible women in the FT-She 100, appearing year after year in large group photographs of students and teachers; thanks to her love of the pen and her magnetic attraction to committees, her work is fairly-well documented; but her private life remains mainly hidden and since neither she nor any of her three siblings had children that part of her story seems destined to remain untold.

Hélène Reynard, King’s College Archives

Hélène was born in Vienna in 1875, the daughter of Marcus Reinherz, a wool merchant, and his wife, Mina Schapira. When she was still a small child, she emigrated to the UK, with her parents, two older sisters, a younger brother and an aunt. They settled in a large double fronted house in Bradford and Hélène went to Bradford Girls Grammar School. She was clearly smart, winning a scholarship to Girton College, Cambridge in 1893. Her brother, Otto, went up to Trinity College one year later, also with a scholarship.

Cambridge life

Hélène studied Moral Sciences, which in the 1890s covered moral philosophy, logic, economics and psychology. Women’s rights were part of the unofficial syllabus. The Cambridge Women’s Suffrage Association had been up and running for nearly ten years and, a few weeks before Hélène went up to Cambridge, women in New Zealand became the first in the world to be given the vote. Her course finished in the summer of 1897 so she still might have been in Cambridge on 21st May of that year when riots broke out as the University considered whether or not to grant women full degrees. (Predictably, the decision from the all-male voters was ‘no’.)

After graduating Hélène moved to London, where she acquired secretarial and bookkeeping skills and worked for several women’s clubs. She also headed to Dublin for a year to study for an MA at Trinity College, Dublin. In 1904 she found herself back at Girton when she was appointed the junior bursar, beating forty applicants to the job. It involved running the residential side of the college and doing some teaching. The following year she was elected to the committee of the Cambridge Association for Women’s Suffrage, joining Margaret Bateson, by then Margaret Heitland. She listened to speeches from Millicent Fawcett and attended NUWSS meetings in London. When The Englishwoman was launched in 1909, partly in response to the formation of the Women’s Anti-Suffrage League, she contributed several essays. One of the most notable was on the ‘Lessons of the Women’s College’, where she made a heartfelt plea to value the life experience women gained from their time at university as well as their academic learning.

Hélène started travelling up to London to run classes on ‘Committee Work and the Conduct of Public Business’ at 92 Victoria Street, the location of the offices of the Women’s Institute. (This was a London women’s club founded in 1897, not to be confused with the far better-known National Federation of Women’s Institutes, founded in 1915.) In 1912 her first book was published, ‘Business Methods and Secretarial Work for Girls and Women’. The future was looking busy and bright when family commitments pulled her back to Bradford.

Running the family business

In 1912, her family set up the Bradford Wool Extracting Company, with Hélène’s father and brother acting as directors alongside a Mr Newton. The business was in financial difficulties almost immediately and Hélène had no choice but to head home and try to sort out the mess. On 4th October 1913 she wrote to resign from her job at Girton ‘with the greatest possible regret’:

‘I will have to live at home and take a share in the management of my father’s factory. I can hardly say how much I shall regret severing my official connection with the college and discontinuing the work which has been the interest and the pleasure of my life for so many years.’

Although the family business must have taken up a lot her time, during the war years Hélène, now with the Anglicised surname of Reynard, immersed herself in local politics. She was secretary of the Bradford Women Citizen’s Association and Secretary of the Women’s Industrial Interests Society. In 1915 she addressed the Bradford NUWSS on Women in Business. She spoke at a conference of the Northern Union of the Association of Teachers of Domestic Subjects in Leeds and in 1918 became a member of the new incarnation of the NUWSS, the National Union of the Society for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC), later serving on the Committee from 1921 to 1923. She also kept writing for the Englishwoman, recommending that educated women consider taking jobs managing institutions like schools or hotels where they would be well-paid and had real business responsibilities.

From duck egg to navy blue

In 1920 Marcus Reynard died and the company was wound up. Hélène used some of her inheritance to endow the Hélène Reynard Scholarship for Economics at Girton in 1921. However, rather than returning to Cambridge to work, she took a job in Oxford as the first full-time and salaried Treasurer and Secretary of Somerville College. Her stint there was to be short. She was recommended by John Maynard Keynes for a post of lecturer at King’s College, London and in 1925 applied to become Principal Administrative Officer of the Department of the Household and Social Science at King’s College for Women. A reference was requested from Girton: the role meant responsibility for 100 students, looking after their academic careers, welfare and social activities. It was a live-in job, managing a large non-resident staff, ‘four of whom are men’. Was Hélène up to it?

In the view of Girton College, the answer was clearly ‘yes’. The reference highlighted how solicitous Hélène had been for the general welfare of the students and how keenly she interested herself in their general activities.

‘She worked with all her colleagues without friction and without fuss and yet was well able to maintain her point of view. Her judgment, unusually wide experience and her obvious sincerity should win her the respect of her colleagues at King’s College as they have invariably done in the past.’

She got the job.

From Department to College

Campden Hill Road runs up from Kensington High Street and Notting Hill. The buildings of what was once the Household and Social Sciences Department are about a third of the way along. Now they house exclusive flats but a century ago they were the lodgings for around 100 students (all women).

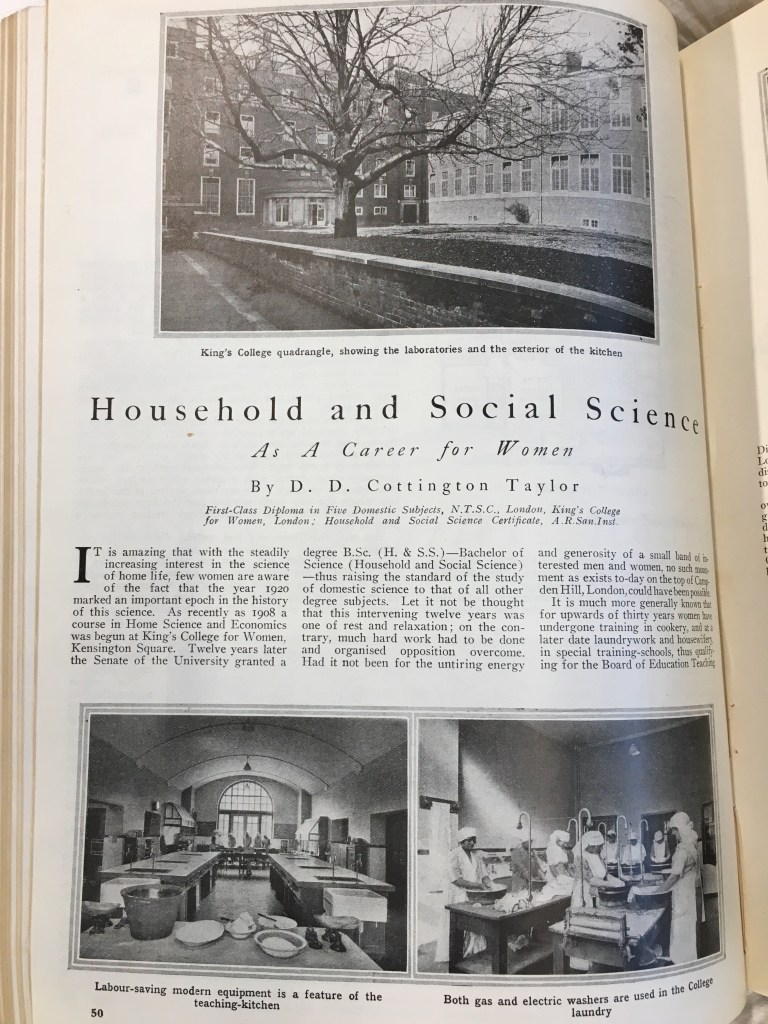

King’s College for Women first instituted a course on Home Science and Economics in 1908 and in 1920, women were able to get a B.Sc in Household and Social Science. Dorothy Cottington Taylor studied there and wrote about it in Good Housekeeping in 1923.

“For a long time it was difficult to overcome the erroneous idea that if a girl was too stupid to qualify for a degree or undertake work requiring a high degree of intelligence, she should train as a teacher of domestic science,” she wrote (though quite frankly that was still the attitude when I was at school in the 1980s.). The department sought to dispel this myth, with labs for physics, biology and bacteriology and classes in social and economic history, physiology and principles of economics and business affairs.

When Hélène arrived one of the first issues she was faced with was the poor state of the teaching of this last topic. Up until 1922, Mildred Ransom had been teaching business affairs part time but a full-time post was created by combining it with economics and she was let go. Her replacement was not a success: results rapidly went south and by the time Hélène joined in 1925 only half the candidates were managing to pass. Hélène immediately took on a chunk of the workload, teaching Economic History. In 1926 she took overall charge and the results started to improve.

There was also the question of the Department’s status with the University to resolve as part of a review of the wider constitution. The decision was made to elevate the Department to the status of an independent College. The University statutes were updated in 1928 and the new King’s College of Household and Social Sciences (KCHSS), University of London was born.

For Hélène it meant a new job title, Warden. Now her job was to build the reputation of the new College, and increase the number of students by bringing academic credibility to the study of Household and Social Sciences. Under her leadership over the next twenty years the College grew in both scale and scope. A new wing was built in 1930, the Physics building was extended and the Teaching Kitchen almost doubled in size in 1931. The College was expanded once again in 1935.

Professionalising the domestic

Despite these efforts, the College was still usually referred to as a training college, rather than an academic institution that prepared women to embark on a career teaching domestic science if further training was undertaken. Speaking on ‘Careers for Women trained in domestic science’ in 1927, Hélène gave four reasons why educated girls from the Universities had such a poor regard for the study of domestic science and they are all still valid to some extent.

- Boys were not taught domestic science so the girls had the suspicion that it must be an inferior subject

- It was assumed that there was nothing in it that merited the attention of educated women

- They did not want to be seen to be buying in to the dictum that ‘Woman’s place was in the Home’

- The jobs available to them in this sphere were badly paid and likely to remain so

She drew unfavourable comparisons between the attitude to hotel management in the UK and Switzerland. While in the latter hotel-keeping was considered an art, London alone, had hundreds of hotels, boarding houses and restaurants crying out for efficient management. The business case

She sought to increase the credibility of her College and its mission through three principle routes.

The first was establishing herself in the world of women’s university education, both the outcomes for students and its wider management. She feared that for many women who graduated from university, unless they were destined for one of the professions, there were not the same opportunities as there were for men, deemed out of scope for many of the university Appointment Boards that helped men onto the career ladder. She was on the Business and University Committee, formed by Lady Rhondda to further the cause of women at work.

She was a member of the Federation of University Women and President of the London branch from 1929-1934. She chaired the Student Careers Association for ten years from 1927-1937. She was President of the London Association of University Women and a member of the University Women’s Club.

The second was economics, with a particular focus on a more scientific approach to designing the home to increase the efficiency of women’s work. She was Chair of the Household Service committee of the National Council of Women and wanted to see domestic science experts in the offices of every architect and builder and in every municipal authority. She worked alongside Ethel Wood, Dorothy Cottington Taylor and Caroline Haslett on the submissions to the Fifth International Congress on Scientific Management, held in Amsterdam in 1932 and the Sixth held in London in 1935. Other participants included Winifred Raphael from the National Institute of Industrial Psychology and Edith Pratt, the Chief Woman Inspector at the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.

She was a Fellow of the Royal Economics Society and in the 1930s managed to write Institutional Management and Accounts (1934); ‘What is a Balance Sheet?’ (1935) and ‘Book-keeping in Easy Stages’ (1937) supported by her secretary, Dore Hustler, to whom she later left xxx in her will. In 1938 she helped found the Institutional Management Association, an industry body for women working across a range of domestic administration roles including college bursars, wardens, housekeepers, dieticians and school matrons.

These two areas overlapped with her wider focus on gender equality. Soon after Hélène arrived in London she joined the Women’s Provisional Club and was a committee member in 1927 and 1928, working alongside women making their way in advertising, theatrical management and the law. Lady Rhondda asked her to be part of the Six Point Group, though does not seem to have joined; she was, however, a guest at her celebratory dinner in March 1933, where she shared a table with Claribel Spurling, WWI codebreaker and Warden of Crosby Hall, and Alys Pearsall Smith Russell. She was active in the re-constituted NUWSS, the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, speaking at a London meeting in 1926 on ‘What the Vote has done.’ She chaired the Women’s Employment Federation in 1936. As if that wasn’t enough, she was also an examiner for the Civil Service between 1929 and 1939.

It is hardly surprising that with this full and wide-ranging agenda she had little time for a private life.

Wartime re-organisation

Even before the outbreak of the Second World War, contingency planning had started to look at options for re-locating London students. In late 1939, the College re-located to Cardiff and then moved again to Leicester in 1940. Hélène connected with local women’s groups, speaking at the Soroptimist Club on the role of the State and commerce ahead of the post-war transformation. Education, free meals, free milk, public health services and subsidised housing should be provided by the State; all large-scale nation-wide enterprises such as railways, mines and electricity should be nationalised. Anything approaching monopoly status should be placed on a semi-public footing. There should be no private trade in armaments or drink (!!) Everything else should be left to private enterprise with adequate safeguards to prevent the exploitation of workers. With this approach, it would be harder to make large fortunes but possible for those with ‘initiative daring and enterprise’ to make ‘moderate fortunes’.

When students finally returned to Kensington in 1946, there were many challenges to address including a shortage of accommodation. By then Hélène had retired, worn out and suffering from ill-health. She went to live with her one of her sisters in Warwick Gardens but kept writing. Her final book, ‘Domestic Science as a Career’, was published just before she died, on 27th December 1947.

Her memorial service at St Mary’s Abbot’s Church in Kensington on 20th January 1948 was very well attended, with well over 100 people including representatives from the many committees and associations to which she had devoted her time and energy and students past and present. ‘During the twenty years of her wardenship, the college, owing to her untiring energy and devotion, expanded greatly both in the number of students and in the scope of its work’, noted The Times. However, her contributions were quickly forgotten and although she is included in the ODNB, she doesn’t get a mention in the history of the College.

Hélène’s articles in The Englishwoman can be read on line – more details can be found in Resources. Other writing includes ‘Varsity Cinderellas’ in The Weekly Dispatch 16/1/1927

Other sources include:

Girton College Archives

Guardian 25/3/1909; The Times 21/10/1912; Common Cause 12/2/1915; 4/2/1927; 12/10/1928; International Women’s News October 1938; Leicester Evening Mail 15/4/1942; The Times 22/1/1948; Kensington News and West London Times 23/1/1948

Good Housekeeping June 1923 ‘Household and Social Science’ by Dorothy Cottington Taylor

‘King’s College of Household & Social Science and the Household Science Movement in English Higher Education c.1908-1939’ – thesis by Nancy L Blakestad (1994)