Born Agnes Beere Smith; known as Mrs A.B. Marshall / Agnes Bertha Marshall

Sector: Food and Beverages

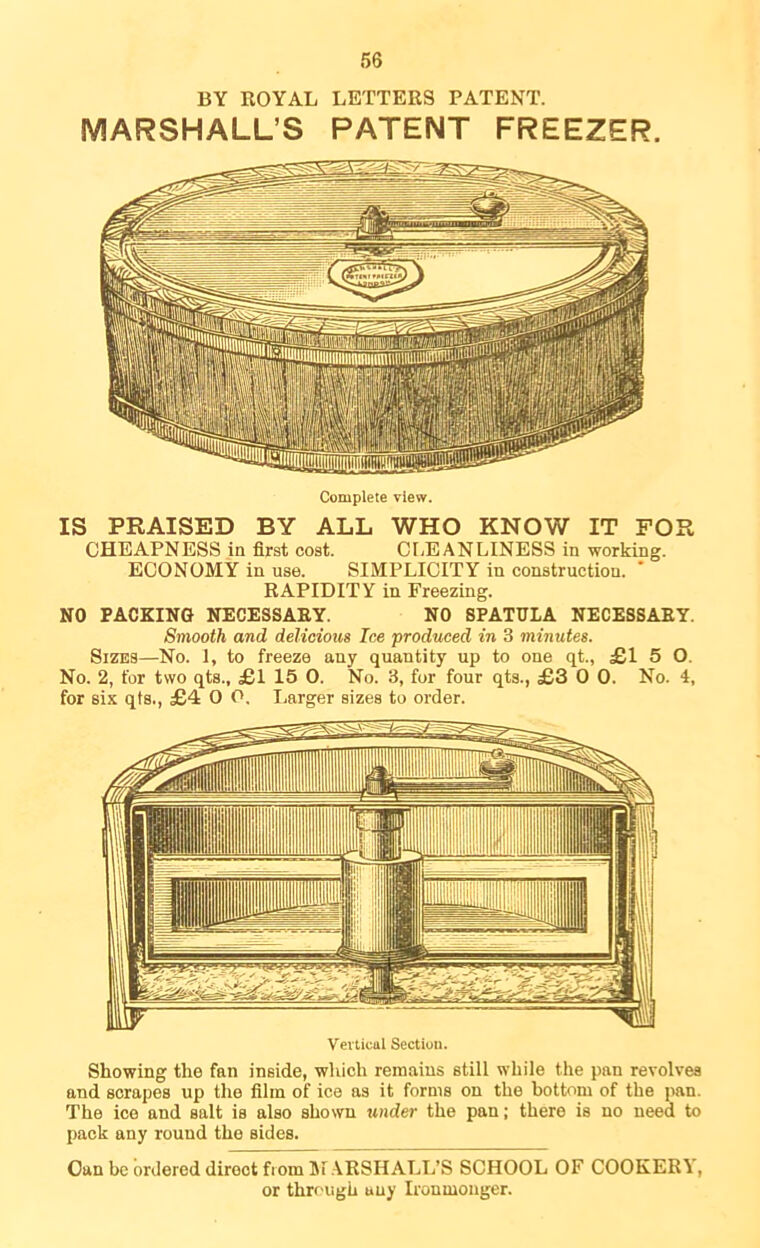

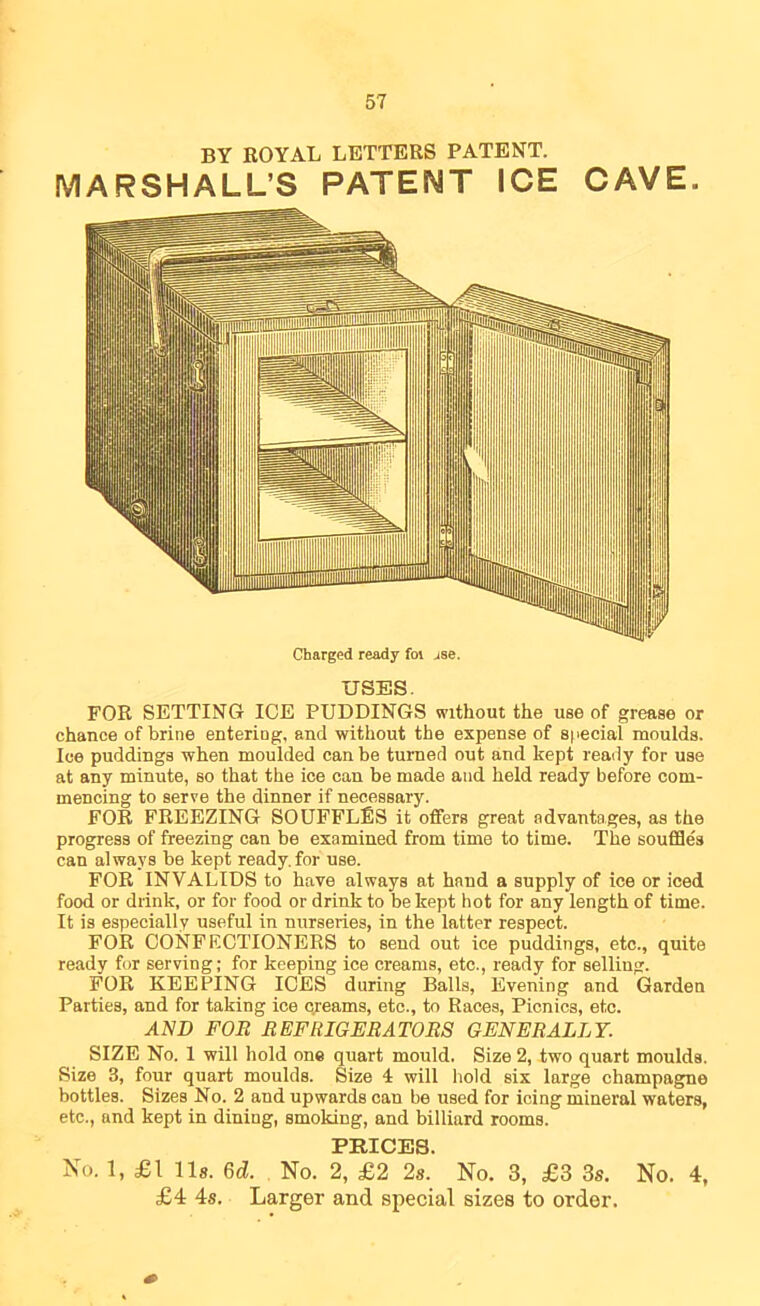

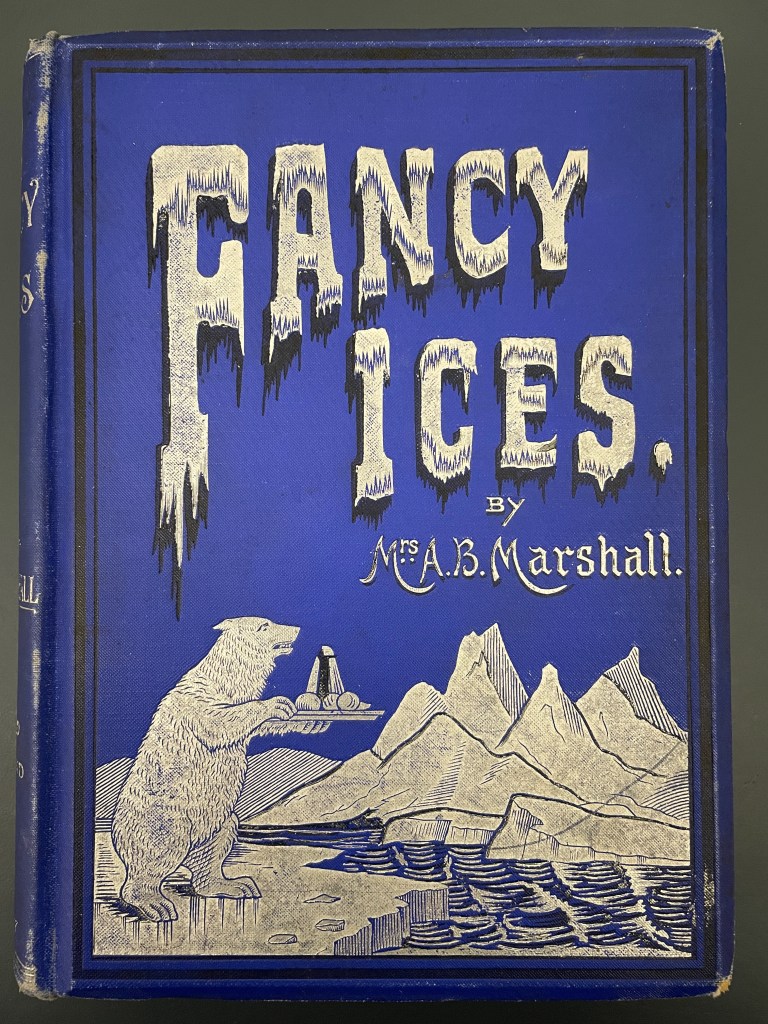

Agnes Marshall is the 85th entry in the FT-She 100 and I feel I should have found her a lot sooner. Food historians, writers and some of Britain’s top chefs have long been singing the praises of this entrepreneurial chef. In the late 19th century Agnes published two best-selling books on ice cream chock full of inventive recipes and was the first person to serve ice-cream in a cornet. She patented an ice cream maker, an ‘ice cave’ (basically a freezer) and an ice breaker. And she advocated for using liquefied gas in the ice cream making process more than century before Heston Blumenthal’s use of liquid nitrogen hit the headlines. (His state-of-the-art ice cream maker has a Victorian crank handle instead of an ‘on’ switch in homage to her). These achievements have earned her the title ‘the Queen of Ices’.

Agnes’s life in the freezer is only part of the story. She was a brilliantly successful businesswoman, building a food and hospitality empire in partnership with her husband. She taught hundreds of students, sold branded ingredients and a wide range of kitchen equipment and published a regular food-focused paper. Within a decade of opening her eponymous cookery school, Mrs A.B. Marshall was a name that could be found on the shelves and in the cupboards of households across the land.

Agnes’s life was of particular fascination to another famous cook, Fanny Cradock. In 1976, she wrote ‘The Sherlock Holmes Cookbook’ and drew heavily on Agnes Marshall’s recipes. She explained why she took on the project:

[The Victorian era] ‘contained special appeal to me since it gave us the woman who wrote everything contained in Escoffier’s Guide to Modern Cookery some years before this masterpiece of his was published’.

She was particularly intrigued by Agnes’s origins: who was this woman, now largely forgotten, who had once been at the forefront of British cookery? She planned to do some detective work and write a book about her. It never materialised but she was right to think there were mysteries to unravel.

A commemorative window for Agnes Bertha Marshall in a Pinner church states her date of birth as 24th August 1855 and her marriage certificate says her father was John Smith, a clerk. All of these ‘facts’ are false and the truth, uncovered as a result of some great detective work by Terry Jenkins in 2018 (see sources) is much more interesting.

Agnes was born on 24th August but in 1852, not 1855. Smith was her mother’s surname. Her middle name was Beere, not Bertha, probably her father’s surname. In April 1878, Agnes gave birth to a daughter, Ethel. She gave her occupation as domestic servant and Ethel took her mother’s surname, with her father’s surname, Doyle, as her middle name.

Five months later Agnes married Alfred Marshall. In March 1879, while she was pregnant with their first child, Alfred, who had set up as a wine merchant, was sentenced to six months in prison for embezzlement.

In an interview in 1886, Agnes’s husband, Alfred, claimed she had made a thorough study of cookery ever since she was a child (quite possible, though mainly in households where she was working) and had practised at Paris and Vienna under celebrated chefs (highly unlikely). The couple had the vision and the skills to take a big risk in 1883 and buy the Laverne cookery school, (possibly somewhere Agnes had been working), we will probably never know how they found the money.

Venturing forth

The cookery only other cookery school of any significance in London at the time was the National Training School of Cookery in South Kensington. After the Great Exhibition of 1851, there was a series of small international exhibitions. There was one in 1873 for which a kitchen was purpose-built for cookery lectures and demonstrations. When the exhibition finished, many were keen to maintain this culinary centre and now the school covered everything from scrubbing tables to straining stock.

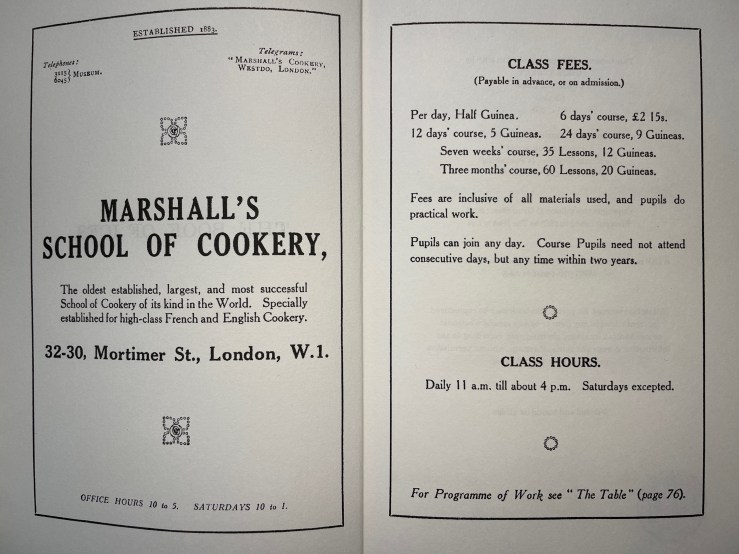

The Marshalls saw an opportunity to offer lessons in what they referred to as ‘high-class cookery’. They bought the Laverne cookery school on Mortimer Street as a going concern, though it’s not clear what they got for their money, since they ‘virtually..had to start afresh’. They re-branded it and re-located it from 67 to 30 Mortimer Street. The new Marshall’s School of Cookery offered lessons every day except Saturday, from 10-4pm. Employers could send their cook along to a single lesson to brush up on a particular area for 10 shillings. For around £20, a woman (and it usually was women) who wanted to be a cook could take a three-month course covering the whole art of cookery. To put this in context, a good salary for a cook at that point was £25 a year.

Business was slow to start with: for the first couple of days they had no pupils at all, but gradually business picked up, with 20-40 pupils a day. By 1885, the school was boasting that thousands of pupils passed through its doors each year.

At a very early stage, ladies who heard about the school would approach them to see if they could help them find a cook so the Marshalls set up a ‘registry of cooks’, or an employment exchange. Ex-pupils of the school could join the registry free, while other cooks had to pay. If a job resulted, both the cook and the employer paid a fee based on the annual salary. Demand exceeded supply: in the first two years of operation, 6,500 women applied for cooks but only 3,700 cooks offered themselves for positions.

Alfred Marshall said later that they ended up losing money because employers did not pay the fees owed. The registry also resulted in Agnes becoming embroiled in a libel case. In 1886, a 52-year old man called William Wandby was sentenced to a week in jail for publishing ‘thirteen defamatory libels’ about Agnes Bertha Marshall. He claimed his wife had answered an advertisement for a cook and returned the papers she needed to complete with payment but received no response and that hundreds of others had been victimised in the same way. He pleaded guilty, offering in mitigation that he had been discharged from a lunatic asylum and could not control himself.

The Book of Ices (1885)

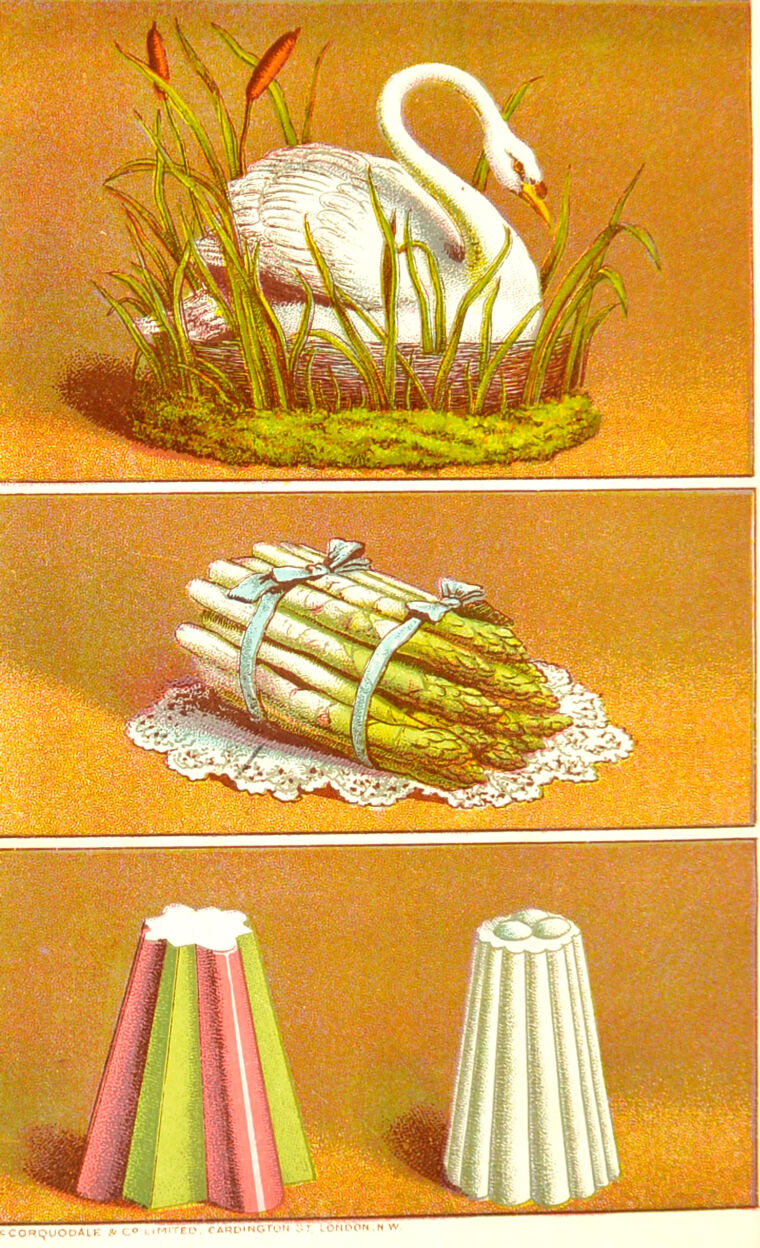

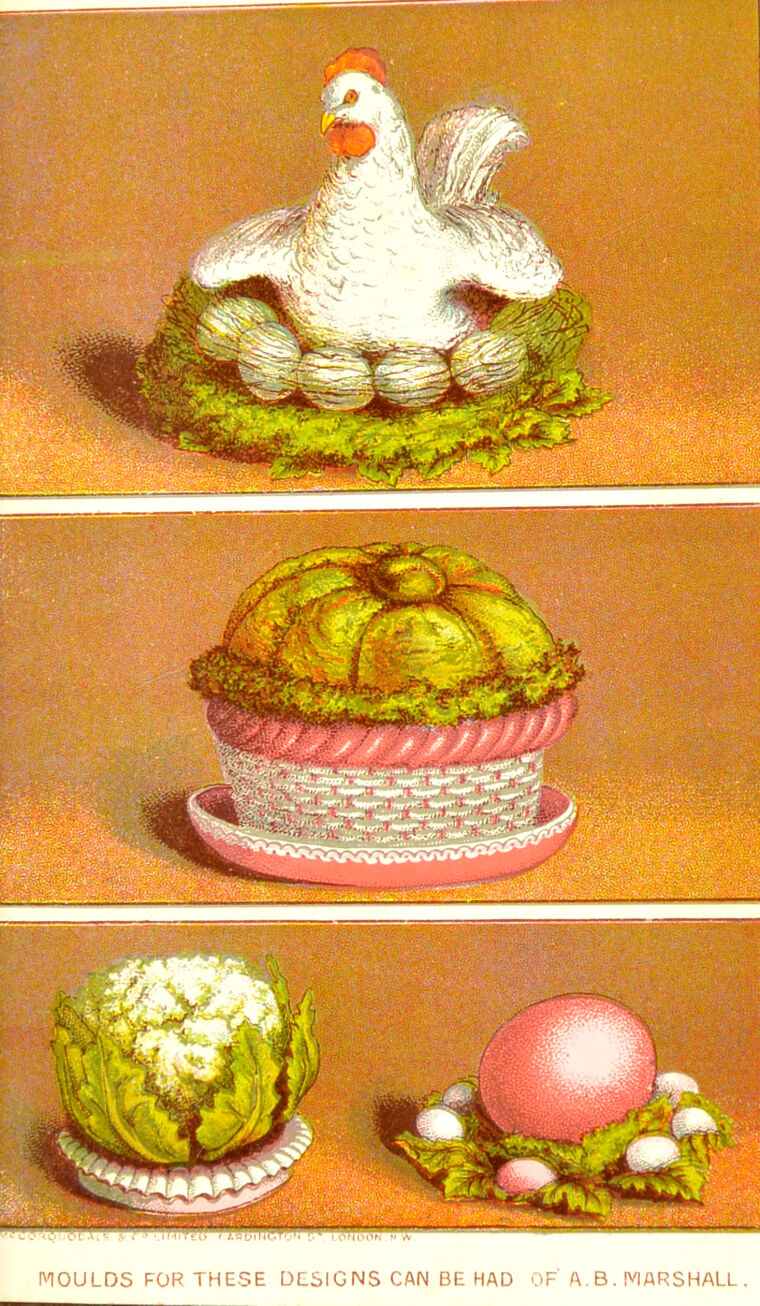

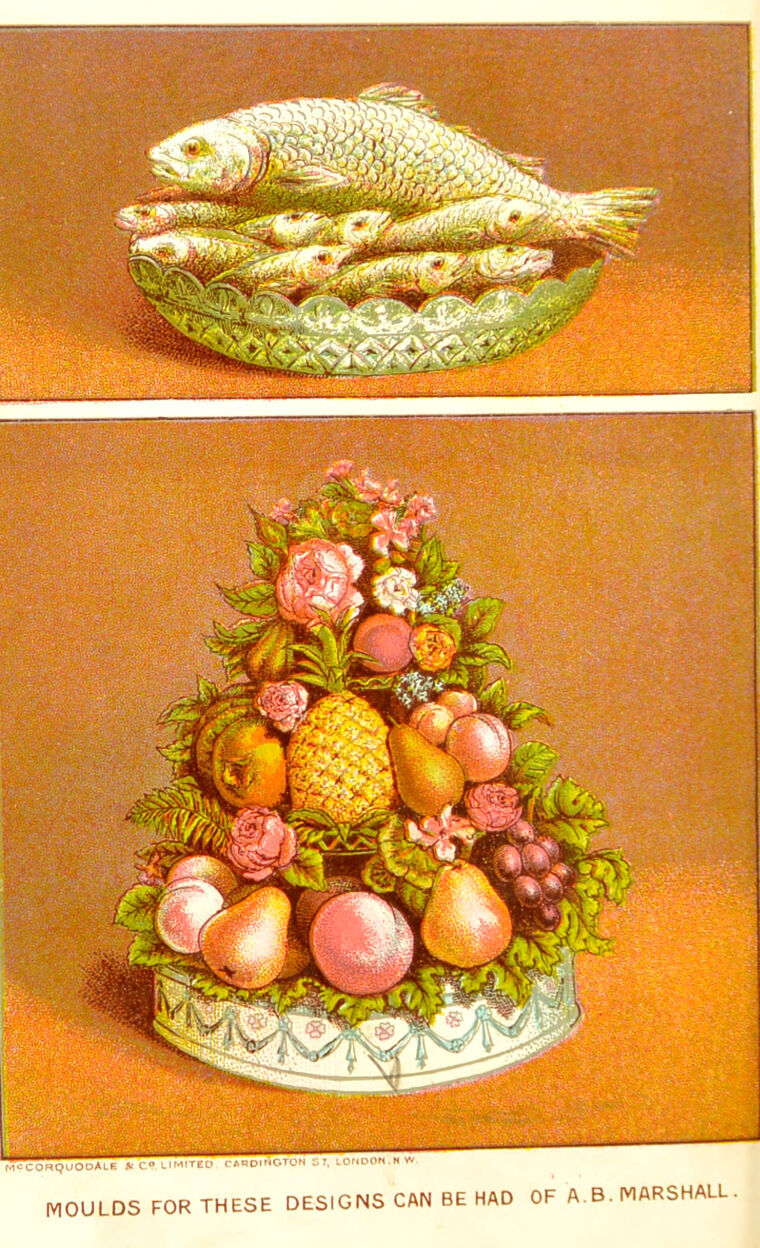

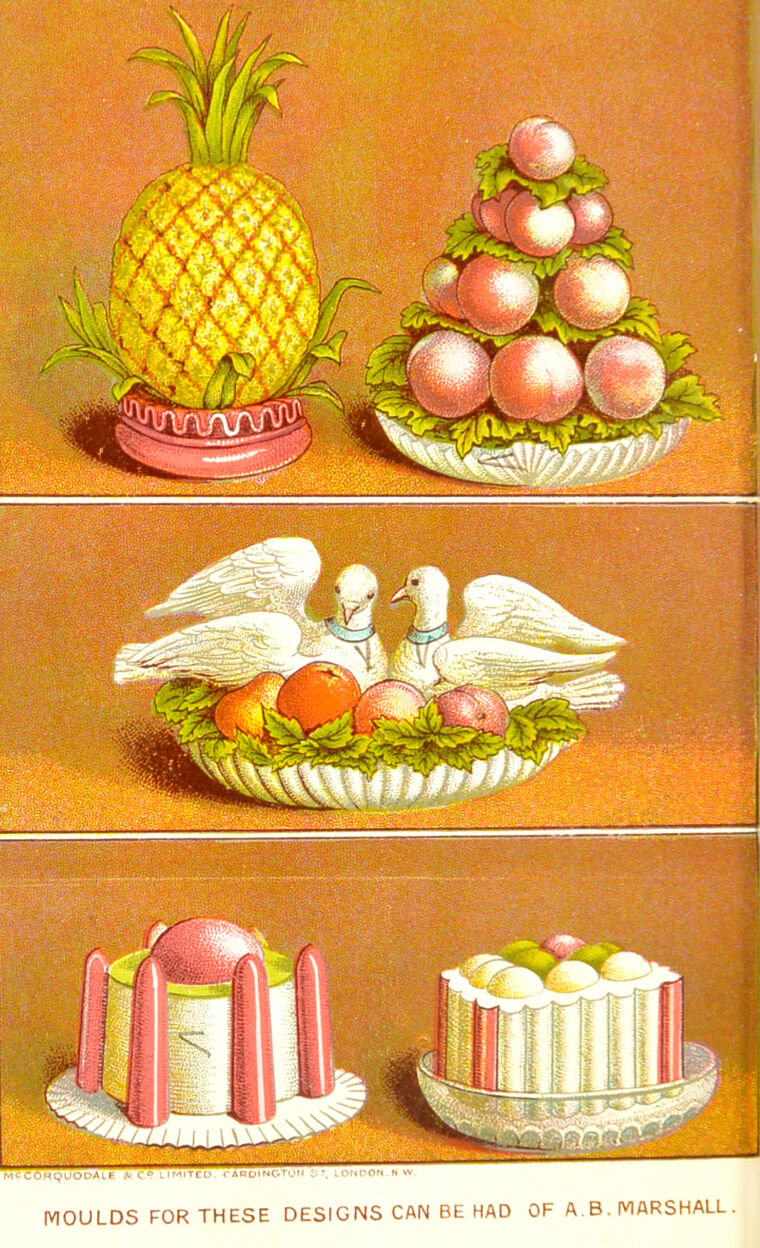

The registry of cooks was not the only additional income stream they were working on. In 1885 Agnes published her first book. ‘The Book of Ices’ had 117 recipes for ice creams, water ices, sorbets, iced soufflés and dressed ices. and four pages of colour illustrations.

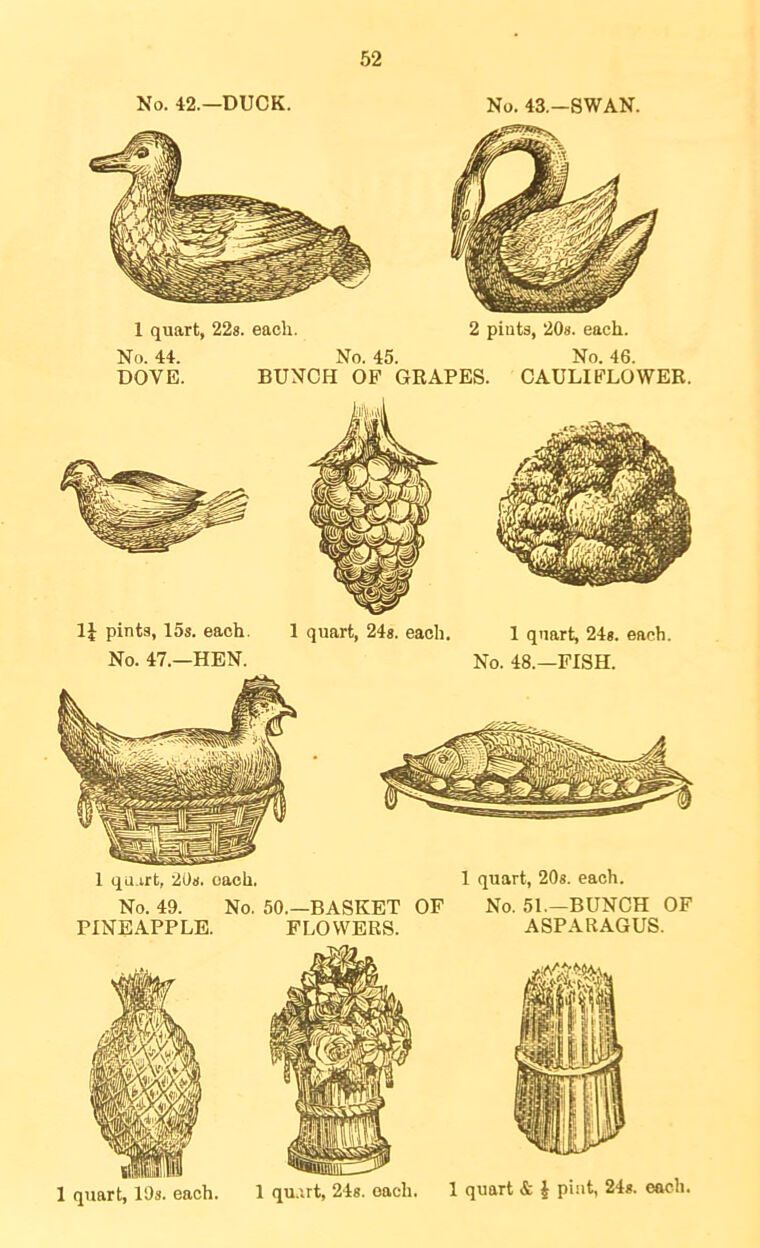

I loved reading through the recipes (anyone fancy curry soufflés for pudding?) and seeing the colour pictures of elaborate desserts, but what is most striking is that in the short time since the school had opened, the Marshalls had developed an extensive range of ingredients and equipment and these were all on display in the last section of the book.

Many recipes required the use of a Marshall product: Marshall’s Finest Leaf Gelatine, Cane Sugar or Noyeau Syrup; or one of their liquid food dyes (Carmine, Sap Green Saffron) or a paste dyes (Apple Green; Cherry Red; Damson Blue; Apricot Yellow; Coffee Brown); or a concentrated essence (vanilla, pineapple, almond, banana, lemon, ratafia, pear, citron). They needed to be churned in the Marshall patent freezer, packed into a Marshall mould, frozen in a Marshall ice cave and then could be served in a fancy basket, available from Marshalls. Marshalls could provide were ice-breakers, wooden pots and freezing salt which ‘produces more intense cold than any other’.

Of the 64 pages, twenty pages are taken up with advertisements for products that could be supplied by Marshalls. It is a masterclass in cross-selling. The basement of number 30 was used for storing and packing up all the products and by 1887 Marshalls needed to expand into the next-door building to have enough space for all the products it was selling and distributing.

Brand building

In 1886, the name of Mrs A.B. Marshall gained greater visibility through the launch in June of The Table, ‘A Weekly Paper of Cookery, Gastronomy, Food, Amusements &c’. It cost 3 pence and in its 16 pages could be found new recipes for High Class dishes and Plain English Dinners and the upcoming programme of lessons at the cook school. Though there was some fiction and society gossip in each issue, much of the content was food-related.

The paper listed the cost of fruit, vegetables, fish and meat at retail and wholesale markets and shared menus from recent dinner parties. There were references to new food trends: One of Agnes’s earliest articles was about the joy of bananas and the wider accessibility she thought would come with a new refrigerated transport vessel. She could well have been one of the first people to write about food vending machines, or as she called them Automatic Candy Shops. ‘In railway stations and elsewhere adults and children may be seen all day long putting pennies into money boxes fixed to large cast-iron apparatuses and drawing therefrom packets of toffee and chocolate.’

In ‘The Boudoir Table’, Agnes advice doled out hostessing advice in a letter to an imaginary friend, Dorothy. “There is nothing newer and there can be nothing prettier than the fairy lights..” “Some new fish plates have a huge John Dory spread over their entire surface painted in colours like a dying dolphin. I cannot say I admire these.” “The rich millionaires’ wives in America have of late been making such a tremendous display of diamonds that I fancy it will soon become unfashionable to wear any jewellery at all.”

Agnes also weighed in on weightier matters like food waste, food hygiene and the way the effectiveness of food distribution systems affected food pricing. When it came to the perennial ‘servant question’, unbeknownst to readers she was drawing on personal experience. Why would girls want to go into domestic service when it is ‘legally and socially looked upon as menial’, she asked. Her suggestion was an Act of Parliament to equalise the relationship from servant and mistress to between employer and employed.

Celebrity chef

By now the Cookery School had garnered many positive reviews and in the autumn of 1886, journalists from The Queen and Pall Mall Gazette ran features on it. Agnes was busy preparing her next book, ‘Mrs A.B Marshall’s Book of Cookery’, a weighty tome with 468 pages and 70 illustrations. As well as the recipes there were plenty of model menus and a guide to seasonal buying. Ahead of its publication she started touring the country demonstrating how to make ‘A Pretty Luncheon.’

It was a tour de force: supported by two assistants in the space of two hours Agnes prepared eight complicated dishes: lobster mayonnaise with aspic jelly; chaudfroid of pigeons in cases; grilled chicken and tartare sauce; a parmesan soufflé omelet; a Maraschino jelly; little nougats and cream; and strawberry and vanilla ice cream. When the food was cooked, it was sent around so the audience could try it. She wore a white dress and apron; both were still spotless when she finished.

First she travelled north to Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle and Edinburgh and then around the south, to Bristol and Exeter. They were hugely successful: ‘it is not the object of her conjuring to mystify but to make clear.’ She took over large venues and attracted fashionable audiences. Of her demonstration in London, one paper wrote that ‘there are very few who have not heard of her School of Cookery in Mortimer-street, commenced under very modest auspices and now raised by her energy and enterprise to its present large proportions.’

The book launch in 1888 was a huge success. ‘Here is a volume of the kind that may fairly claim to originality and that has the rarer merit even of absolute trustworthiness’, said one review. By the time it was re-printed in 1895 it had sold 30,000 copies.

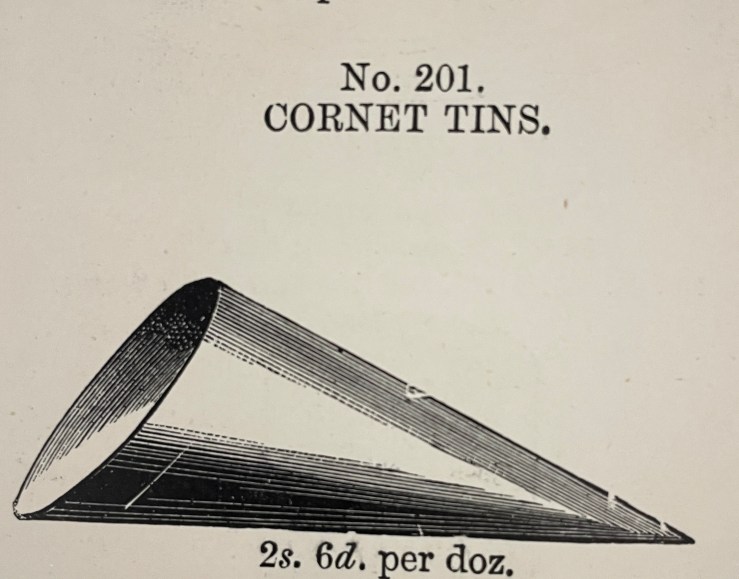

The arrival of the cornet

Agnes’s 1888 book also marked a landmark in the history of ice cream because it was here that she gave a recipe for ‘Cornet with Cream’, a critical step on the path to the ice cream cone we know today. The cornet is made by making a paste from chopped almonds, flour, sugar, egg and orange flower water; partially cooking it and then bending it around a cornet tin. Then it can be filled with ice cream and eaten with a fork.

There is no picture of the cornet in this book but the tin has been added to the array of moulds.

In 1894, Agnes published what would be her last cookery book, devoted to ice-creams. It repeated only one recipe from ‘The Book of Ices’. The new desserts included Ellen Terry Melon (apple and melon sorbet served on meringue), Timbales named for Queen Victoria’s daughters (Empress Frederick and Princess Christian), and Nelson Greengage Cream. Puddings were designed to look like cucumbers and mushrooms. The Marshall product range had expanded and so now the recipes might also call for a splash of their Silver Rays Rum.

Once again, she presented a cornet, this time called the Margaret Cornet.

Since this was not made of waffle or designed to be held in the hand, it is not an ice-cream cone as we would know it but it was an important step on the way, so the next time you are walking along enjoying an ice cream cornet, think of Agnes.

Continued expansion

During the 1890s, Agnes’s celebrity grew and grew and the business flourished in parallel. She continued to venture out of London. After one demonstration in Liverpool in 1892, a Liverpool journalist was in positive ecstasies about her performance, wishing for an idyll by the Latin poet Horace to record her ‘dainty demonstration’ ‘Mrs Marshall is rapidly raising cookery to a high place among the fine arts and the poet and the painter of her delightful methods are not far hence.’ By now she had swapped her white and mauve dress for pink silk and diamonds.

One of the most popular events were Agnes’s ‘entire dinner lessons’. They did what they said on the tin, with at least one recipe prepared for each course, a total of around 12 to 14 in total. ‘The Queen‘ ran a feature on them in 1887 and during the 1890s they grew in scale and reputation. In 1896, the Lady’s Pictorial ran a full-page spread with photographs of some of the dishes as well as one of the class in progress. This is not a great reproduction but you can see how crowded the room is and on the table there is a Marshall Ice Cave and an array of Marshall’s products.

The first one for the winter season of 1899 had seventeen dishes. ‘High though Mrs Marshall’s standard always is, the dinner of Oct 13 struck as as one of the best she has ever set before her pupils’ reported one paper.

By now Marshall’s had dedicated showrooms for its vast product range at no. 32 Mortimer Street, one for Moulds and Knives and other equipment; one for Kitchen Furnishings, Wines and Spirits and French, Italian and American goods. In 1888 Agnes did a publicity tour in the United States and took the opportunity to gather more recipes and snap up some American toasters. They soon became all the rage. ‘The are made of wire and are something like a gridiron that opens’, explained Lady’s Pictorial to its readers. ‘The slides of bread are put between the wires and the toaster is closed and in this way you can quite easily make two or three slides of toast at the same time.’ There was also now a warehouse nearby on Wells Street

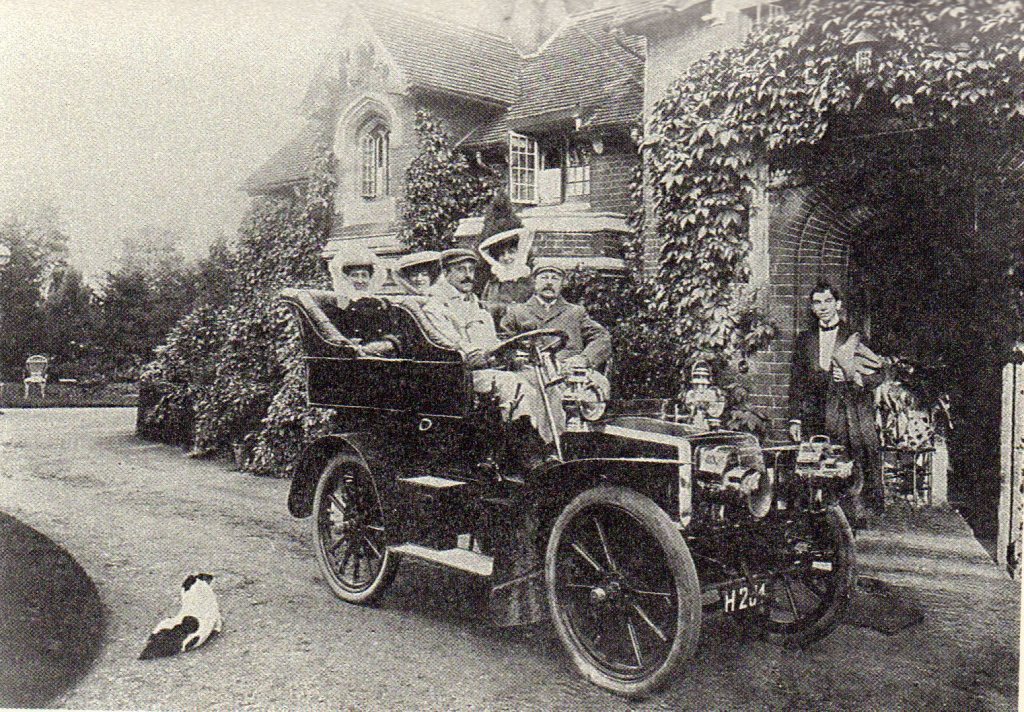

Unsurprisingly, with such a successful business, the family was able to live well. They built a big house in Pinner, The Towers and are thought to have been one of the first local families to have a car.

Sadly Agnes did not have all that long to enjoy her hard-won wealth. Sometime in late 1903 or early 1904 she fell ill, with what was later diagnosed as cancer, and then in the summer of 1904 she had a bad riding accident. These both contributed to her death in the summer of 1905 (though Fanny Cradock was convinced she was murdered by Alfred).

Alfred commissioned the stained glass window with her erroneous date of birth from Ninian Comper but was already moving on. In 1906 he married Gertrude Walsh, who also worked at the cookery school, and they had two children together. He sold the school in 1921 and it continued in business into the 1930s. The Table ran until 1958.

Agnes has always had her devotees, like Fanny Cradock, but she has been restored to wider attention in recent years thanks to the efforts of food historians, particularly Robin Weir and John Deith. An exhibition about her was held at Syon House in 1998 and the London Canal Museum in 1999. In 2013, a compilation of her recipes was re-issued. This summer I am going to honour Agnes by giving one a try.

The Book of Ices, Fancy Ices and Agnes’s comprehensive cookery book from 1888 have both been digitised so have a scroll through, particularly if you want some new (old) ideas for pudding. Some of Agnes’s dishes have been re-created by food historian and blogger Ivan Day. For a fun history of ice-cream, which mentions Agnes, listen to this episode of ‘You’re Dead to Me’.

Sources include:

Pall Mall Gazette 30/3/1886; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 2/11/1886; The Queen 6/11/1886; Birmingham Daily Post 10/8/1887; The Echo 25/10/1887; Lady’s Pictorial 2/11/1899; The Times 11/11/1889; The Queen 13/4/1895; Stamford Mercury 25/12/1896; The Queen 3/9/1898; 21/10/1899; 5/8/1905; Belfast Newsletter 14/8/1905; The Times 30/6/2011

“The Truth about Mrs Marshall”, by Terry Jenkins in Petits Propos Culinaires 112, November 2018, pp. 100-112.

What a fascinating story!

What an inspirational lady Agnes was…….so good to read about her!

LikeLike